КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

The Origins of Management

|

|

|

|

Management as a field of study may be just 125 years old, but management ideas and practices have actually been used from the earliest times of recorded history. For example, 2,500 years before management researchers called it job enrichment, the Greeks learned that they could improve the productivity of boring repetitious tasks by performing them to music. The basic idea was to use a flute, drum, or song lyrics to pace people to work in unison using the same efficient motions, to stimulate them to work faster and longer, and to make the boring work more fun.1 While we can find the seeds of many of today’s management ideas throughout his-tory, not until the last two centuries, however, did systematic changes in the nature of work and organizations create a compelling need for managers.

Let’s begin our discussion of the origins of management by learning about 1.1 man-agement ideas and practice throughout history, and 1.2 why we need managers today.

1.1 Management Ideas and Practice Throughout History

Examples of management thought and practice can be found all throughout his-tory.2 For example, as shown in Exhibit 1, in 5000 B.C. in an early instance of managing information, Sumerian priests developed a formal system of writing

THE HISTORY OF MANAGEMENT

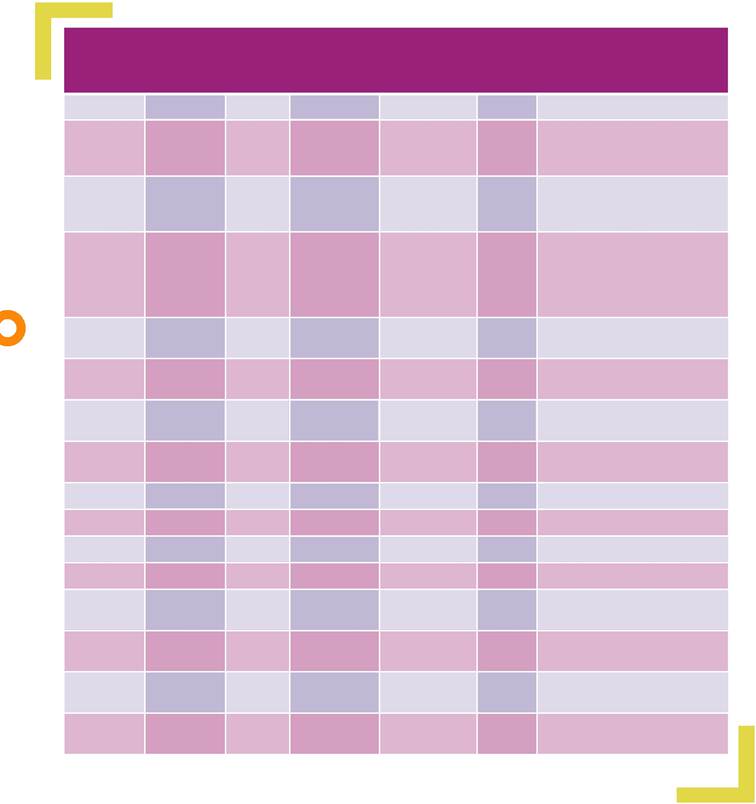

| Exhibit 1 | Management Ideas and Practice Throughout History | ||||||

| ORGANIZING | CONTRIBUTIONS TO | ||||||

| INDIVIDUAL | MAKING | MEETING | PEOPLE, | MANAGEMENT | |||

| OR | THINGS | THE | PROJECTS, AND | THOUGHT | |||

| TIME | GROUP | HAPPEN | COMPETITION | PROCESSES | LEADING | AND PRACTICE | |

| 5000 B.C. | Sumerians | ✓ | Record keeping. | ||||

| 4000 B.C. | Egyptians | ✓ | ✓ | Recognized the need for | |||

| planning, organizing, and | |||||||

| controlling. | |||||||

| 2000 B.C. | Egyptians | ✓ | ✓ | Requests submitted in writing. | |||

| Decisions made after consulting | |||||||

| staff for advice. | |||||||

| 1800 B.C. | Hammurabi | ✓ | Established controls by using | ||||

| writing to document transac- | |||||||

| tions and by using witnesses to | |||||||

| vouch for what was said or | |||||||

| done. | |||||||

| 600 B.C. | Nebucha- | ✓ | ✓ | Production control and wage | |||

| dnezzar | incentives. | ||||||

| 500 B.C. | Sun Tzu | ✓ | ✓ | Strategy; identifying and attack- | |||

| ing opponent’s weaknesses. | |||||||

| 400 B.C. | Xenophon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Management recognized as a | |

| separate art. | |||||||

| 400 B.C. | Cyrus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Human relations and motion | ||

| study. | |||||||

| Cato | ✓ | Job descriptions. | |||||

| Diocletian | ✓ | Delegation of Authority. | |||||

| Alfarabi | ✓ | Listed leadership traits. | |||||

| Ghazali | ✓ | Listed managerial traits. | |||||

| Barbarigo | ✓ | Different organizational | |||||

| forms/structures. | |||||||

| Venetians | ✓ | Numbering, standardization, | |||||

| and interchangeability of parts. | |||||||

| Sir Thomas | ✓ | Critical of poor management | |||||

| More | and leadership. | ||||||

| Machiavelli | ✓ | Cohesiveness, power, and lead- | |||||

| ership in organizations. | |||||||

| Source:C. S. George, Jr., The History of Management Thought (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1972). | |||||||

(scripts) that allowed them to record and keep track of the goods, flocks and herds of animals, coins, land, and buildings that were contributed to their tem-ples. Furthermore, to encourage honesty in such dealings, the Sumerians insti-tuted managerial controls that required all priests to give written accounts of the transactions, donations, and payments they handled to the chief priest. And just

THE HISTORY OF MANAGEMENT

| like stone tablets and animal-skin documents, these scripts were first used to | |

| manage the business of Sumerian temples.3 Only later were the scripts used for | |

| religious purposes. | |

| One thousand years after the Sumerians, the Egyptians recognized the need | |

| for planning, organizing, and controlling, for submitting written requests, and | |

| for consulting staff for advice before making decisions. The practical problems | |

| they encountered while building the great pyramids no doubt led to the devel- | |

| opment of these management ideas. For example, the enormity of the task they | |

| faced is evident in the pyramid of King Cheops, which contains 2.3 million | |

| blocks of stone. Each block had to be quarried, cut to precise size and shape, | |

| cured (hardened in the sun), transported by boat for two to three days, moved | |

| onto the construction site, numbered to identify where it would be placed, and | |

| then shaped and smoothed so that it would fit perfectly into place. It took | |

| 20,000 workers 23 years to complete this pyramid; more than 8,000 were | |

| needed just to quarry the stone and transport it. A typical “quarry expedition” | |

| might include 100 army officers, 50 government and religious officials, and 200 | |

| members of the king’s court to lead the expedition; 130 stone masons to cut the | |

| stones; and 5,000 soldiers, 800 barbarians, and 2,000 bond servants to trans- | |

| port the stones on and off the ships.4 | |

| The remainder of Exhibit 1 shows how other management ideas and practices | |

| throughout history are clearly related to the management functions in the text- | |

| book. Besides the achievements of the Sumerians and Egyptians, we might note |

King Hammurabi, who established controls, and King Cyrus, who emphasized the importance of human relations; all understood the importance of making things happen (planning, managing information, decision making, and control). Among those who contributed important ideas regarding how to meet the compe-tition (global management, strategy, innovation and change, and designing adap-tive organizations) were Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War, who emphasized the importance of strategy and of identifying and attacking an opponent’s weak-nesses; Diocletian, a Roman emperor, who mastered the art of delegation by dividing the widespread Roman Empire into 101 provinces, which were then grouped into 13 dioceses, which were in turn grouped into four geographic divi-sions; and Barbarigo, who discussed the different ways in which organizations could be structured. The Egyptians furthered our understanding of organizing people, projects, and processes (managing diversity, teams, human resources, and managing services and manufacturing), as did King Nebuchadnezzar, who pioneered techniques for producing goods and used wages to motivate workers; King Cyrus, who used motion study to eliminate wasteful steps and improve pro-ductivity; and Cato, who espoused the importance of job descriptions. Among the forerunners of today’s thinking about leadership (motivation, leadership, and communication) were not only Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus, and Sun Tzu but also Alfarabi and Ghazali, who began defining what it takes to be a good leader or manager; and Sir Thomas More, who, in his book Utopia, emphasized the nega-tive societal consequences associated with poor leadership.

1.2 Why We Need Managers Today

Working from 8 A.M. to 5 A.M., coffee breaks, lunch hours, crushing rush hour traffic, and punching a time clock are things we associate with today’s working world. Work hasn’t always been this way, however. In fact, the design of jobs and organizations has changed dramatically over the last 500 years.

For most of humankind’s history, people didn’t commute to work. In fact, travel of any kind was arduous and extremely rare.5 Work usually occurred in homes or on farms. For example, in 1720, almost 80 percent of the 5.5 million people in England lived and worked in the country. Indeed, as recently as 1870, two-thirds of Americans earned their living from agriculture. Even most of those who didn’t earn their living from agriculture didn’t commute to work. Skilled tradesmen or craftsmen, such as blacksmiths, furniture makers, and leather

THE HISTORY OF MANAGEMENT

| goods makers who formed trade guilds (the historical predecessors of labor | |

| unions) in England as early as 1093, typically worked out of shops in or next to | |

| their homes.6 Likewise, cottage workers worked with each other out of small | |

| homes that were often built in the shape of a semicircle. A family in each cottage | |

| would complete a different production step with work passed from one cottage to | |

| the next until production was complete. For example, since textile work was a | |

| common “cottage industry,” families in different cottages would shear the sheep; | |

| clean the wool; comb, bleach, and dye it; spin it into yarn; and weave the yarn into | |

| cloth. Yet, with no commute, no bosses (workers determined the amount and pace | |

| of their work), and no common building (from the time of the ancient Egyptians, | |

| Greeks, and Romans through the middle of the nineteenth century, it was rare for | |

| more than 12 people to work together under one roof), cottage work was very dif- | |

| ferent from today’s jobs and companies.7 And since these work groups were small | |

| and typically self-organized, there wasn’t a strong need for management. | |

| During the Industrial Revolution (1750–1900), however, jobs and organiza- | |

| tions changed dramatically.8 First, thanks to the availability of power (steam | |

| engines and later electricity) and numerous inventions, such as Darby’s coke- | |

| smelting process and Cort’s puddling and rolling process (both for making iron) | |

| and Hargreave’s spinning jenny and Arkwright’s water frame (both for spinning | |

| cotton), low-paid, unskilled laborers running machines began to replace high- | |

| paid, skilled artisans. Whereas artisans made entire goods by themselves by | |

| hand, this new production system was based on a division of labor: each worker, | |

| interacting with machines, performed separate, highly specialized tasks that | |

| were but a small part of all the steps required to make manufactured goods. | |

| Mass production was born as rope- and chain-driven assembly lines moved work | |

| to stationary workers who concentrated on performing one small task over and | |

| over again. While workers focused on their singular tasks, managers were now | |

| needed to effectively coordinate the different parts of the production system and | |

| optimize its overall performance. Productivity skyrocketed at companies that | |

| understood this. For example, at Ford Motor Company, the time required to | |

| assemble a car dropped from 12.5 man hours to just 93 minutes.9 | |

| Second, instead of being performed in fields, homes, or small shops, jobs | |

| occurred in large, formal organizations where hundreds, if not thousands, of peo- | |

| ple worked under one roof.10 In 1849, for example, with just 123 workers, Chicago | |

| Harvester (the predecessor of International Harvester) ran the largest factory in | |

| the United States. In 1870, the Pullman Company, a manufacturer of railroad | |

| sleeping cars, was the largest, with only 200 employees. Yet, by 1913, Henry Ford | |

| employed 12,000 employees in his Highland Park, Michigan factory alone. With | |

| the number of people working in manufacturing having quintupled from 1860 to | |

| 1890, and with individual factories employing so many workers under one roof, | |

| companies now had a strong need for disciplinary rules (to impose order and | |

| structure), and, for the first time, they needed managers who knew how to organ- | |

| ize large groups, work with employees, and make good decisions. | |

| Review 1 | |

| The Origins of Management | |

| Management as a field of study may be just 125 years old, but management | |

| ideas and practices have actually been used since the beginning of recorded his- | |

| tory. From the Sumerians in 5000 B.C. to sixteenth-century Europe, there are | |

| historical antecedents for each of the functions of management discussed in the | |

| textbook: making things happen; meeting the competition; organizing people, | |

| projects, and processes; and leading. Despite these early examples of manage- | |

| ment ideas, there was no compelling need for managers until systematic changes | |

| in the nature of work and organizations occurred during the last two centuries. | |

| As work shifted from families to factories, from skilled laborers to specialized, | |

| unskilled laborers, from small, self-organized groups to large factories employing | |

| thousands under one roof, and from unique, small batches of production to large | |

| standardized mass production, managers were needed to impose order and |

THE HISTORY OF MANAGEMENT

| structure, to motivate and direct large groups of workers, and to plan and make | ||

| decisions that optimized overall company performance by effectively coordinating | ||

| the different parts of organizational systems. | ||

| Evolution of Management | ||

| Before 1880, business educators taught basic bookkeeping and secretarial skills, | ||

| and there were no books or articles published about management.11 Over the | ||

| next 25 years, however, things changed dramatically. In 1881, Joseph Wharton | ||

| gave the University of Pennsylvania $100,000 to establish a department to edu- | ||

| cate students for careers in management. By 1911, 30 business schools, includ- | ||

| ing those at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the University of California, | ||

| had been established to teach managers how to run businesses.12 In 1886, | ||

| Henry Towne, president of the Yale and Towne Manufacturing Company, pre- | ||

| sented his ideas about management to the American Society of Engineers. In his | ||

| talk entitled “The Engineer as Economist,” he emphasized that managing people | ||

| and work processes was just as important as engineering work, which focused | ||

| on machines.13 Towne also argued that management should be recognized as a | ||

| separate field of study with its own professional associations, journals, and liter- | ||

| ature where management ideas could be exchanged and developed. Today, | ||

| because of the forethought and efforts of Joseph Wharton and Henry Towne, if | ||

| you have a question about management, you can turn to dozens of academic | ||

| journals (such as The Academy of Management’s Journal or Review, Administra- | ||

| tive Science Quarterly, the Strategic Management Journal, and the Journal of | ||

| Applied Psychology), hundreds of business schools and practitioner journals | ||

| (such as Harvard Business Review, Sloan Management Review, and the Academy | ||

| of Management Executive), and thousands of books and articles. In the remainder | ||

| of this discussion, you will learn about other important contributors to the field | ||

| of management and how their ideas shaped our current understanding of man- | ||

| agement theory and practice. |

After reading the next four sections, which review the different schools of manage-ment thought, you should be able to

1 explain the history of scientific management.

2 discuss the history of bureaucratic and administrative management.

3 explain the history of human relations management.

4 discuss the history of operations, information, systems, and contingency man-agement.

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2014-12-17; Просмотров: 835; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!