КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

Table of Contents 1 страница

|

|

|

|

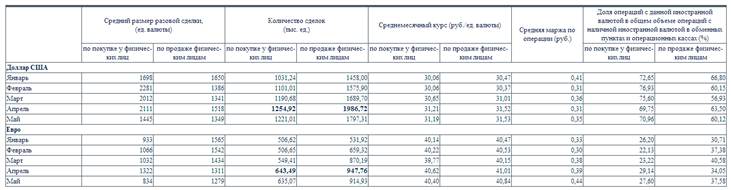

Отдельные показатели, характеризующие операции с наличной иностранной валютой в уполномоченных банках в 2013 году

1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 7.0 7.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 Acknowledgments About the Author

for my Em

“How on earth are you ever going to explain in terms of chemistry and physics so important a biological phenomenon as first love?”

—Albert Einstein

1.0

Beginnings are tricky things. I’ve been staring at this blank page for forty-seven minutes. It is infinite with possibilities. Once I begin, they diminish.

Scientifically, I know beginnings don’t exist. The world is made of energy, which is neither created nor destroyed. Everything she is was here before me. Everything she was will always remain. Her existence touches both my past and my future at one point—infinity.

Lifelines aren’t lines at all. They’re more like circles.

It’s safe to start anywhere and the story will curve its way back to the starting point. Eventually.

In other words, it doesn’t matter where I begin. It doesn’t change the end.

1.1

Geeks are popular these days. At least, popular culture says geeks are popular. If nerds are hip, then it shouldn’t be hard for me to meet a girl.

Results from my personal experimentation in this realm would suggest pop culture is stupid. Or it could be that my methodology is flawed. When an experiment’s results are unexpected, the scientist must go back and look at the methods to determine the point at which an error occurred. I’m pretty sure I’m the error in each failed attempt at getting a girl’s attention. Scientifically, I should have removed myself from the equation, but instead, I kept changing the girl.

Each experiment has led to similar conclusions.

Subject: Sara Lewis, fifth grade, Method: Hold her hand under the table during social studies, Result: Punched in the thigh.

Subject: Cara Whetherby, fifth grade, second semester, Method: Yawn and extend arm over her shoulder during Honor Roll Movie Night, Result: Elbowed in the gut.

Subject: Maria Castillo, sixth grade,

Method: Kiss her after exiting the bus,

Result: Kneed in the balls.

After Maria, I decided my scientific genius was needed for other, better, experiments. Experiments that would write me a first-class ticket to MIT.

I’m tall and ropey with sandy blond hair so fine it’s like dandelion fluff—the kind of dork that no amount of pop culture can help. Which is how I already know how this experiment will end, even as my hand reaches out to touch the girl standing in front of me at Krispy Kreme donuts.

There was a long line when I walked in this morning, so I’d been passing the time by counting the ceiling tiles (320) and figuring the ratio of large cups to small cups stacked next to the coffee (3:2). I’d been counting the donuts in the racks (>480) when I noticed the small tattoo on the neck of the girl in front of me.

It’s a symbol—infinity. There’s a cursive word included in the bottom of one of the loops, but I can’t read it because one of the girl’s short curls is in the way.

Before I realize what I’m doing, I sweep away the hair at the nape of her neck. She shudders and spins around so fast that my hand is still midair. Flames of embarrassment lick at my earlobes, and I wonder if I should be shielding my man parts from inevitable physical brutality.

“What’s your problem?” Her hand cups her neck, covering the tattoo. Her pale skin flushes and her pupils are black holes in the middle of wild blue seas, but since I’m not coughing up my nuts, I’m already doing better with this girl than any before.

She’s waiting for me to explain.

It takes too long to find words. She’s too beautiful with that raven-hued hair and those eyes. “I wanted to see your tattoo.”

“So, ask next time.”

I nod. She turns back around.

The curl has shifted.

The word is “hope.”

“Rapido, Chuck. J’s pissing his pants because we’re going to be ‘tardy,’” Greta says, using her shoulders to wedge the door open so she can make air quotes around James’s favorite word. “God, it smells good in here.”

Greta McCaulley has been my best friend since our freshman year at Brighton. On the first day of Algebra II, Mr. Toppler held a math contest, like a spelling bee only better. I came in second, one question behind Greta. Since then, her red hair, opinions, and chewed-up cuticles have been a daily part of my life. She has a way of ignoring the stuff about me that makes others want to punch me. And she’s equal parts tenacity and loyalty—like a Labrador/honey badger mutt.

She’d also beat the crap out of me if she knew I’d just thought of her as a hybridized breed of animal.

Outside, her boyfriend James unfolds himself from the cramped backseat of my car, and rips open the heavy doors. “People of Krispy Kreme, I will not be made tar—” He takes a quick breath and loses his concentration. Krispy Kreme’s sugary good smell remains invincible.

Greta stands beside me in line, while James drifts toward a little window to watch the donuts being born in the kitchen. Greta and James have been together since the second quarter of ninth grade. If I wanted to continue to hang out with Greta, her Great Dane of a boyfriend would have to become part of my small circle of friends.

Actually, it’s not a circle. It’s a triangle. I’d need more friends to have a circle.

The girl with the tattoo steps up and orders a glazed and a coffee. She’s about our age, but I don’t know her, which means she must go to my sister’s high school, Sandstone. It’s for the regular kids. I go to Brighton School of Math and Science. It’s for the nerds.

Greta leans into my shoulder, and I know I’m not supposed to notice because a) we’ve been friends for a long time, b) James is four feet away, and c) I just fondled a stranger’s neck, but Greta’s left breast brushes against my arm.

“So what’s with the girl?” she asks. “I saw her turn and—”

My ears feel warm. “Shhh.”

Mercifully, Greta whispers, “I thought she was going to punch you.”

“Me, too.”

“What’d you do?”

“She has a tattoo,” I say, shrugging.

“And?”

“And, I may have touched it.”

Greta’s mouth hangs open, a perfect donut.

“Fine. I touched it.”

“Where?” Greta quickly turns and scans the girl. “Oh, thank God,” she breathes, touching the correlating spot on her own bare neck. “I thought maybe it was a tramp stamp.”

I must look blank because Greta points to her lower back, just below the waistline of her khaki uniform skirt.

“God, no,” I say, too loudly. The girl with the hope tattoo glances over her shoulder. Greta and I both look at our shoes.

James steps in front of us, and for once I’m thankful that the width of 1 James = 2 Charlies + 1 Greta. His large frame blocks us from the girl’s glare. James taps the face of his watch.

“I know,” I say. “Look, both of you go back to the car. I’ll be right there. We have plenty of time to make it before the first bell.”

They turn to leave just as the girl is stepping away from the counter, coffee in one hand and donut in the other. I should let her walk away and be thankful she didn’t punch me, but without thinking, I touch her arm as she goes by. I can feel the muscle of her bicep tighten under my fingertips.

I’m locked in place, like when an electric shock seizes all the muscles in your body so that the only thing that can save you—letting go of the electrical source—is the only thing you can’t do.

“Yes?” she asks, her jaw looking as tight as her bicep feels.

“I wanted to apologize.”

“Oh,” she says. Her muscles relax. “Thanks.”

She smells amazing. At least, I think it’s her and not the warm donut in her hand. Either way, I have to force myself to focus on what I was about to say.

“So, I’m sorry.” Now, walk away. Go, Hanson. “But I’m afraid you’re mistaken about infinity. Infinity is quantifiable. Hope is immeasurable.”

Her expression shifts, like Tony Stark slipping into his Iron Man mask. She shakes her arm free from my slack grip. “So if it can’t be measured, I shouldn’t count on it? That’s bleak, man. Very bleak.”

She turns and pushes through the door.

Subject: Girl with the hope tattoo, first day of senior year,

Method: Grope her neck. Follow with a lecture on topics in advanced mathematics,

Result: No physical harm, but left doubting whether I’ll ever figure this relationship stuff out.

1.2

I pull into the school parking lot as James finishes the last of his donuts. He ate all six. He also ate one of mine. Greta hasn’t touched hers yet. She’d been fixated on the scenery of the suburbs dying off and the city rising up, the same scenery we’ve seen every day for three years. The early morning sun winks through the haze of southern humidity clinging to the buildings like a wet blanket. I guess it is hard to believe this is our last first day of school at Brighton. Only 179 more morning drives like this one.

I spent the time wondering what someone would do with boundless hope. I mean, that’s a lot of hope.

“What’d you think of that tattoo, Gret?”

Greta turns away from the window, one ginger brow arched. “I think it’s none of our business.”

“Yeah, but don’t you think that’s maybe an excessive amount of hope?”

“Depends what you’re hoping for. Why do you care? And what was with that stellar display of social ineptitude back there?”

“I don’t care.” Except, why hope? And why can’t I stop thinking about the way the soft skin of her neck felt under my fingertips? And why did she look so sad just before she stormed away? I need more data. “Let’s just call it an experiment.”

James laughs, leaning forward between the front seats. “Thought you’d agreed to let the big boys do that research,” he says, flexing the thick muscles of his forearms.

Greta snorts, but I catch her watching the muscles dance.

“I’d offer to get y’all a room, but I wouldn’t want James to be tardy.” They both blush. “Oh, but look at that,” I say, pulling into an open spot, “three whole minutes to spare. Maybe I should have stopped?”

And the punch I’ve been waiting for all morning finally lands on my shoulder, solid enough to rock me sideways a bit.

“Oh, shut up, idiot,” Greta says, shaking out her fist, “or I’ll destroy that proof you’ve been working on in seven seconds flat.”

“You can’t disprove shit,” I say, but a sliver of doubt wedges in my mind.

That proof is my ticket to winning over Dr. Martin K. Bell, god of mathematics, who will take me under his wing at MIT next year and mentor me, until one day he’ll proclaim, There is nothing more for me to teach you. The student has outshone the teacher. Shortly after, I’ll receive the Nobel Prize.

I’ve got a lot riding on this proof.

“ I only need six seconds,” James counters, a wide, white smile lighting his dark brown face.

They bicker about who can dismantle three years of my work the fastest as we climb out of the car. Eager to change the subject, I point at Greta’s uneaten donut.

“Ungrateful much, Gret? ‘Take me to donuts,’ you said. So I did.” I fold my arms across my chest in mock protest.

James swoops in and tries to pluck it from her hands. “I’ll eat it. I’m still hungry.”

Greta’s attention is diverted. “How can you be hungry, J? You’ve eaten more calories than a cheerleader eats in a week.”

“What cheerleader?” James says, pretending to look around for one. Brighton doesn’t have cheerleaders. We’d need sports teams to justify them. Mathletes don’t count, even if they think they do. “Show me the cheerleader?”

They’re a teenage version of a middle-aged married couple. She shoulders her large bag, and sighs. “Why do I put up with him?”

I shrug. “Beats me, but someone may as well enjoy that donut. I almost got beaten up by a girl getting it for you.”

“If it means that much to you…” She shoves the entire donut in her mouth at once, and smiles at me, her freckled cheeks full of donut.

“Did you see that?” James asks as she walks away, his voice soft, maybe even reverent. James thinks most everything Greta does is amazing—even the gross stuff—which gives me hope for a positive experiment result in the future.

Not infinitely hopeful, of course. That’s just nonsense.

1.3

At lunch, we eat under an apple tree in the courtyard. There is a plaque dedicating the tree to a former principal with her favorite quote, “Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton asked why.”

James leans against the plaque as he compares our schedules for this year. He and I had a class together this morning. I’ve got advanced physics with Greta after lunch, and we’ll all meet up again at the end of the day for senior English.

“Wonder who the new target is this year,” James muses, cramming his schedule card back in his pocket.

The target in question would be the English teacher. Brighton goes through English teachers like Hogwarts devours Defense Against the Dark Arts teachers.

“We can deduce it’s a female,” I point out, tapping the name on my schedule card. Ms. Finch—Senior English.

“Hope she’s not like Ms. Kelly the fem-bot,” James says with a shudder.

Greta is busy finding something in her bag. “Not this already,” she says. Her face is mostly buried in there, but the part of it I can see looks annoyed. “Promise me you dorks will stay focused on what’s important.”

“I am always focused,” I say.

Greta looks up. “True,” she says, a flicker of her fierce protectiveness crossing her face. Two years ago, I took on too much—too many classes, mathletes team captain, a junior internship with the university physics department, and a shot at the national science fair. I failed an assignment in chemistry. I’d never failed before. My mind went a little berserk.

I only remember pieces (which Dr. McCaulley, Greta’s psychologist mom, says is normal), but I was convinced I could work out the glitch in my chemistry experiment if I could give it one more try. Of course, in order to do that, I needed to break into Dr. Stormwhiler’s lab. It was one a.m., and I may have triggered an alarm when picking the lock on the disused gym door.

Alone inside the school, I panicked and called Greta. Her mom called the police and met them here. Greta found me, catatonic by that time, in the storage room off one of the labs.

If Greta hadn’t been there to pull me back from the edge, and tell me to stop being a whiny quitter, I’d have left school and given up on all my ambitions.

Turning her attention toward James, Greta says, “ You promise to stay focused.” She punctuates the sentence by poking him in the arm with a pencil she’s just pulled from her bag.

“Hey, I’m focused.”

Greta scoffs. James scowls at the apple he’s about to bite into. “Whatever.”

Satisfied, Greta starts scribbling computations in her notebook while James rubs a bruise on his apple and mumbles loud enough for me to hear, “I’m focused. Focused on carrying out a proud high school tradition.”

Brighton is a STEM academy. The mission statement, emblazoned on another plaque by the front office, states our time here is meant to prepare us for futures in fields related to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Our motto (yep, another plaque) is Aut viam inveniam aut faciam. Meaning, “I’ll either find a way or make one.”

So, we’ve found a way to reduce the time we have to spend on things like poetry and literature by making the English teachers hate their jobs here. It’s not hard either. It only takes a little shove to start a ball rolling before inertia takes over. The constant tide of teachers means that little learning goes on in the English classroom.

It’s a simple equation. No teacher = no English. No English = more time for things that matter. Like math.

We take seats near the back of the English room. I study the bookshelves lining all four walls and crammed full of books. I don’t recognize any of the titles, which isn’t saying much. Above the bookshelves are paintings. Big ones of trees with people laughing as they hang in the branches. Small ones of books stacked neatly. Tall paintings with stacks of books in the act of tumbling over. Forty-two paintings. They are all different, but the same.

Forty-two paintings, but zero teachers.

At Brighton, class starts on time. In fact, the advanced physics teacher, Mrs. Bellinger, will write you up for tardiness for being on time. She says “on time” is late. James is in love with Mrs. Bellinger.

“This does not bode well,” James says, preparing to launch into an assault on the English teacher’s lack of respect for timeliness. Greta shushes him by pinching his arm.

And then, walking in, grimacing while wiping one hand on her skirt and carrying a spilling cup of coffee in the other hand, is this year’s target, Ms. Finch. She’s got long black hair and is wearing a knee-length black skirt and a white shirt open at the neck to reveal the creamy complexion of her throat. Let’s just say she doesn’t look like any of the other teachers here.

“Sorry for being tardy,” the woman says. James chokes a little on his superiority.

Ms. Finch swears under her breath as the coffee sloshes from the overfilled cup onto the hand clutching it. She switches hands and wipes the other hand on her skirt. Looking up at the twenty-two sets of eyes staring at her, she blushes.

“I’ve been so…let’s just say I haven’t been sleeping well lately,” she says raising the coffee cup and spilling more. “Guess I was a little overexcited when I refilled.”

Déjà vu sweeps over me. Where have I seen her before?

No. Not her exactly.

The girl with the hope tattoo.

“Let’s get started. Better late than never,” she says. She pulls a stool over to her podium, picks up a small paperback novel and begins to read.

I can’t tell you what she reads to us because I’m too busy finding all the similarities and differences between our new teacher and the girl in the donut shop. It becomes a puzzle, like the “Find the Difference” puzzles in Highlights when I was little.

They have the same eyes and jet-black hair. This one is taller and older, but not by much. I wonder if she has a tattoo, and what it might say.

When she finishes reading, Ms. Finch closes the book and looks out over us. “I’d like to begin,” she says, “by letting you all in on a little secret.”

Students shift closer in their seats.

“I know all about you.” She pauses to let that sink in. “I know you think your precious math and sciences have all the answers and what I have to offer”—she waves the paperback in her hand—“is useless. But you’re wrong.”

There’s a faint hiss in the room.

“There are some things in life that cannot be explained with logic. They cannot be understood through dissection. They are what they are—good, bad, or epically crappy. Sometimes they are all those things at once.” She walks up the center aisle as she speaks. Like lambs to the slaughter, our eyes follow her.

“I know what you all do with English teachers here at Brighton. I know,” she says, turning at the back of the classroom to be sure she has our attention. “And I say: Bring. It. On.”

1.4

I toss my keys onto the counter as I walk into the kitchen. Someone is rummaging behind the refrigerator door for the good stuff Mom hides in the back.

I assume it’s my younger sister, Becca. She’s a sophomore at Sandstone, although how she got that far, I’m not sure. She’s wicked smart, but getting good grades doesn’t motivate her. Mom swears Becca has an eidetic memory. There’s no conclusive evidence eidetic memory exists, according to scientific research, but Becca can recite almost word for word every book she’s read since she was nine. And she has seven overflowing bookcases in her room alone.

“Dibs on the last Milky Way, Bec.”

I hear a soft curse from inside the fridge. Becca doesn’t curse.

“Possession is nine-tenths of the law.” The girl with the tattoo closes the refrigerator door, then winces when she recognizes me, the doofus who manhandled her from the donut place.

“You?” I glance around. Yep. In my kitchen. Did she follow me? No. That’s dumb. It was hours ago that we were at Krispy Kreme, even if it was only moments ago that I was thinking of her in English. I take in her simple purple T-shirt and the way her skinny jeans hug her calves. “What are you doing here?”

“Getting a snack,” she says. Her inflection sounds like she’s choosing her tone with each word. She grins, deciding to play it cool. “Becca said I should help myself, and we don’t have any good stuff at my house.” She waves the candy bar like a magic wand.

“Becca Hanson?” Becca doesn’t have friends. In fifteen years, she’s had three. One moved away when she was eight. The other two were imaginary. I am calculating the statistical improbability of Becca choosing this girl—of all the girls in our town, this beautiful, tattooed girl—to be her friend when Becca comes flying down the stairs.

“Charlie! You’re home.” Her face floods with relief.

“You have to meet Charlotte. She’s my partner for this project I have to do, even though I told Mr. Bunting I’m not good at group projects, because they include other people, and other people don’t like me.”

Becca twists her brown hair around her index finger as she carries on. “He didn’t listen, and because she’s new in school and doesn’t know about the whole me and people thing, Charlotte said she’d love to work with me.” Becca’s voice wavers a little.

It’s not that people dislike Becca. Rather, people make Becca anxious, and the anxiety makes her build these impregnable walls around herself. It also causes babbling spells that make mere mortals cringe. I haven’t seen her this upset since the Harry Potter series came to an end.

She’s still rambling. “She said I should call her Charley instead of Charlotte, and I said, ‘No, because, my brother’s name is Charlie and it would be weird.’ And she said, ‘Okay.’ So, I’m just calling her Charlotte.” Becca runs out of breath and stops.

I take a second to drink in this other Charley, from her glossy curls down to her once-white Converse sneakers, covered in Sharpie doodles of what appear to be feathers. That stupid déjà vu feeling steals over me again.

Charlotte interrupts my inspection of her. “I like the idea of a new town and a new me. Charlotte is perfect. Back home I didn’t get a choice, you know? Charley is what my older sister calls me, so everyone followed suit.”

Sister? It’s the last piece of evidence I needed to prove my theory. Forty-two paintings. The English teacher. Matching sets of blue eyes. This isn’t a doppelgänger coincidence. They must be related.

“You look like my English teacher.”

Charlotte’s smile tightens as she studies me. “You must go to Brighton, then. Impressive. And possibly useful.” She tosses the candy bar from hand to hand and says, “I’m Charlotte Finch.”

Our eyes meet and she fumbles the candy bar. When she bends to retrieve it, I catch a glimpse of the tattoo.

“Why useful?”

“ Possibly useful.” Her ink-stained fingers flit across the back of her neck. “Like you said, I can’t count on things I can’t measure. ” The acidic inflection she loads onto the statement makes me cringe.

“I just meant hope isn’t part of any infinite set.”

One of Charlotte’s thin, dark eyebrows disappears under the fringe of hair on her forehead.

I sigh. “Most people don’t understand infinity. It bugs me.”

Charlotte nods. “Busybodies. That’s my pet-peeve.” She smiles. “Oh, and pets named Peeve.”

Becca guffaws beside me. I’d forgotten about her. “This is my pet, Peeve,” she mumbles to herself. I notice that her finger is so twisted in her hair that she has to yank to get it out. Before she can do any damage, I help her unwind it.

I can feel Charlotte watching me. It is both satisfying and horrifying.

Once Becca’s free, Charlotte suggests they get back to work. Becca is just about to start with the hair thing again when Charlotte adds, “I’m in desperate need of something to read, and I couldn’t help but notice you have some great books.”

“Sure,” Becca says, smiling. She doesn’t smile much, so it’s easy to forget, but when Becca smiles she looks like a whole new person.

Charlotte flicks the candy bar at me with the warning, “Think fast.”

I grab for it, but the Milky Way smacks me in the center of the chest and falls to the floor. Charlotte laughs, and it sounds like fingers dancing up piano keys.

I know I should pick it up, but I’m frozen to my spot. When she laughed, something inside my chest shifted. I don’t know what it means, but it feels like I’ve got more room inside myself.

It takes a few minutes after she leaves before I realize that she never told me how I might be useful to her.

1.5

I’ve spent today deflecting James’s repeated pleas for me to join forces with him to start the war against the English teacher.

In computer programming, he gave a moving speech about brotherhood and camaraderie. He spoke of the oncoming tide of literature, and how we could stand by and be crushed by it or rise up and defeat it. He even tossed in a “Semper Fi.”

At lunch, he tries to make me his superhero sidekick.

“You have to help me pull off at least a few stunts. What would Batman be without his Robin? Superman without Lois Lane?”

“I’m a Marvel fan, dumbass. And did you just call me a girl?”

He’s quiet the rest of lunch until I cave and ask, “Why do you care?”

His eyes kind of light up like coals burning low. “It’s a chance to leave a legacy.”

“But I’ve already got a legacy. It’s called being the valedictorian.”

Greta scoffs. “You wish, Chuck. I’ll be the one delivering that speech, thank you very much.”

James sighs and traces the letters of the “why” on the apple tree plaque. He’s not in the top ten of our class. He’s number eleven, and not because he isn’t brilliant, but because he has other priorities that Greta and I don’t, like spending time with his sisters. I sometimes feel like I only think about my sister when she’s right in front of me, but James is always thinking about his—whether they are safe, did they eat their lunches at school, what they got on spelling tests…

“Fine, then,” James says. “It’s not about the legacy. It’s about us doing something together this last year before we all go to college.”

Greta’s smirk falls away.

James’s father passed away six years ago when James was eleven. Greta has explained to me that James’s frustration over people leaving him (both actual and hypothetical) can leak out in strange and surprising ways—like, if he could trap us all in a biodome to keep us together forever, he would. I guess this need of his for us to band together against the English teacher is another of those ways.

Greta squeezes his knee. “We’ve still got all year together.”

“Yeah, man. A year is a long time,” I say, trying to be encouraging. “Twelve months, fifty-two weeks, three hundred sixty-five days, eight thousand seven hundred sixty hours—”

James holds up a hand to stop me. “But this would be something that when we’re old we could look back on and laugh about. Together.”

Greta’s eyes soften. “I’d make a pretty kickass Batwoman, don’t you think?”

James’s face brightens with the smile he gives her.

I snort, and Greta raises a brow at me, daring me, as always, to challenge her. I stuff my trash in my lunch sack and mutter, “I’m no Boy Wonder.”

1.6

I take my seat beside Greta in English and glance at my phone: 2:59:21 p.m. I’ve got bigger worries than James now that I’m about to face Ms. Finch. I’m afraid of what Charlotte may have told her about me.

Hey, I met one of your students yesterday, sis.

Oh, which one?

Charlie Hanson molested my neck in the Krispy Kreme and then told me hope doesn’t exist.

I don’t want to give Ms. Finch the chance to engage in some parameter-setting discussion involving Charlotte. A discussion like, “Don’t ever touch my little sister again.”

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2014-12-24; Просмотров: 347; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!