КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

Derision

|

|

|

|

KNEE-JERK IRONY: The

GREEN DIVISION: To

VIETNAM, SON

WELCOME HOME FROM

Time to escape. I want my real life back with all of its funny smells,

pockets of loneliness, and long, clear car rides. I want my friends and

my dopey job dispensing cocktails to leftovers. I miss heat and dryness

and light. 'You're okay down there in Palm Springs, aren't you?"

asks Tyler two days later as we roar up the mountain to visit the Vietnam

memorial en route to the airport. "Alright, Tyler— spill. What have

Mom and Dad been saying?" T'Nothing. They just sigh a lot. But they

don't sigh over you nearly as much as they do about

Dee or Davie." "0h?" "What do you do down

there, anyway? You don't have a TV. You don't

have any friends—" "! do, too, have friends,

Tyler." "Okay, so you have friends. But I worry

about you. That's all. You seem like you're

only skimming the sur- face of life, like a water

spider—like you have some secret that prevents you from entering the mundane everyday world. And that's fine —but it scares me. If you, oh, I don't know, disappeared or something, I don't know that I could deal with it." "God, Tyler. I'm not going anywhere. I promise. Chill, okay? Park over there—" f'You promise to give me a bit of warning? I mean, if you're going to leave or metamorphose or whatever it is you're planning to do—" "Stop being so grisly. Yeah, sure, I promise." " Just don't leave me behind. That's all. I know—it looks as if I enjoy what's going

know the difference between envy and jealousy.

on with my life and everything, but listen, my heart's only half in it. You give my friends and me a bum rap but I'd give all of this up in a flash if someone had an even remotely plausible alternative."

"Tyler, stop."

"I just get so sick of being jealous of everything, Andy— " There's no stopping the boy. " —And it scares me that I don't see a future. And I don't understand this reflex of mine to be such a smartass about everything. It really scares me. I may not look like I'm paying any attention to anything, Andy, but I am. But I can't allow myself to show it. And I don't know why."

Walking up the hill to the memorial's entrance, I wonder what all that was about. I guess I'm going to have to be (as Claire says) "just a teentsy bit more jolly about things." But it's hard.

tendency to make flippant ironic comments as a reflexive matter of course in everyday conversation.

PREEMPTION: A life-style tactic; the refusal to go out on any sort of emotional limb so as to avoid mockery from peers. Derision Preemption is the main goal of Knee-Jerk Irony.

FAME-INDUCED APATHY: The attitude that no activity is worth pursuing unless one can become very famous pursuing it. Fame-induced Apathy mimics laziness, but its roots are much deeper.

At Brookings they hauled 800,000 pounds offish across the docks and in Klamath Falls there was a fine show of Aberdeen Angus Cattle. And Oregon was indeed a land of honey, the state licensing 2,000 beekeepers in 1964.

The Vietnam memorial is called A Garden of Solace. It is a Guggenheim-like helix carved and bridged into a mountain slope that resembles mounds of emeralds sprayed with a vegetable mister. Visitors start at the bottom of a coiled pathway that proceeds upward and read from a series of stone blocks bearing carved text that tells of the escalating events of the Vietnam War in contrast with daily life back home in Oregon. Below these juxtaposed narratives are carved the names of brushcut Oregon boys who died in foreign mud.

The site is both a remarkable document and an enchanted space. All year round, one finds sojourners and mourners of all ages and ap-pearance in various stages of psychic disintegration, reconstruction, and reintegration, leaving in their wake small clusters of flowers, letters, and drawings, often in a shaky childlike scrawl and, of course, tears.

Tyler displays a modicum of respect on this visit, that is to say, he doesn't break out into spontaneous fits of song and dance as he might

|

were we to be at the Clackamas County Mall. His earlier outburst is over and will never, I am quite confident, ever be alluded to again. "Andy. I don't get it. I mean, this is a cool enough place and all, but why should you be interested in Vietnam. It was over before you'd even reached puberty."

"I'm hardly an expert on the subject, Tyler, but I do remember a bit of it. Faint stuff; black-and-white TV stuff. Growing up, Vietnam was a background color in life, like red or blue or gold—it tinted everything. And then suddenly one day it just disappeared. Imagine that one morning you woke up and suddenly the color green had vanished. I come here to see a color that I can't see anywhere else any more." "Well / can't remember any of it." "You wouldn't want to. They were ugly times—" I exit Tyler's questioning.

Okay, yes, I think to myself, they were ugly times. But they were also the only times I'll ever get—genuine capital H history times, before history was turned into a press release, a marketing strategy, and a cynical campaign tool. And hey, it's not as if I got to see much real history, either—I arrived to see a concert in history's arena just as the final set was finishing. But I saw enough, and today, in the bizzare absence of all time cues, I need a connection to a past of some importance, however wan the connection.

I blink, as though exiting a trance. "Hey, Tyler—you all set to take me to the airport? Flight 1313 to Stupidville should be leaving soon."

The flight hub's in Phoenix, and a few hours later, back in the desert I cab home from the airport as Dag is at work and Claire is still in New York.

The sky is a dreamy tropical black velvet. Swooning butterfly palms bend to tell the full moon a filthy farmer's daughter joke. The dry air squeaks of pollen's gossipy promiscuity, and a recently trimmed Pon-derosa lemon tree nearby smells cleaner than anything I've ever smelled before. Astringent. The absence of doggies tells me that Dag's let them out to prowl.

Outside of the little swinging wrought iron gate of the courtyard

that connects all of our bungalows, I leave my luggage and walk inside. Like a game show host welcoming a new contestant, I say, "Hello, doors!" to both Claire's and Dag's front doors. Then I walk over to my own door, behind which I can hear my telephone starting to ring. But this doesn't prevent me from giving my front door a little kiss. I mean wouldn't you?

Claire's on the phone from New York with a note of confidence in her

voice that's never been there before—more italics than usual. After

minor holiday pleasantries, I get to the point and ask the Big Question:

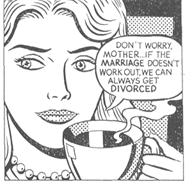

"How'd things work out with Tobias?" 'Comme çi, comme ça. This

calls for a cigarette, Lambiekins—hang on—there should be one in this

case here. Bulgari, get that. Mom's new husbnad Armand is just loaded.

He owns the marketing rights to those two little buttons on push-button

telephones—the star and the box buttons astride

the zero. That's like own- ing the marketing rights

to the moon. Can you bear it?" I hear a click

click as she lights one of Armand's pilfered So-

branies. "Yes. Tobias. Well well. What a case."

A long inhale. Silence. Exhale. I probe: "When

did you finally see him?" "Today. Can you be-

lieve it? Five days after Christmas. Unbelievable. I'd made all these plans to meet before, but he kept breaking them, the knob. Finally we were going to meet down in Soho for lunch, in spite of the fact that I felt like a pig-bag after partying with Allan and his buddies the night before. I even managed to arrive down in Soho early—only to discover that the restaurant had closed down. Bloody condos, they're ruining everything. You wouldn't believe Soho now, Andy. It's like a Disney theme park, except with better haircuts and souvenirs. Everyone has an

|

IQ of 110 but lords it up like it's 140 and every second person on the street is Japanese and carrying around Andy Warhol and Roy Lichten-stein prints that are worth their weight in uranium. And everyone looks so pleased with themselves." "But what about Tobias?"

"Yeah yeah yeah. So I'm early. And it is c-o-l-d out, Andy. Shocking cold; break-your-ears-off cold, and so I have to spend longer than normal in stores looking at junk I'd never give one nanosecond's worth of time to normally—all just to stay warm. So anyhow, I'm in this one shop, when who should I see across the street coming out of the Mary Boone Gallery but Tobias and this really sleek looking old woman. Well, not too old, but beaky, and she was wearing half the Canadian national output of furs. She'd make a better looking man than a woman. You know, that sort of looks. And after looking at her a bit more, I realized from her looks that she had to be Tobias's mother, and the fact that they were arguing loaned credence to this theory. She reminds me of something Elvissa used to say, that if one member of a couple is too striking looking, then they should hope to have a boy rather than a girl because the girl will just end up looking like a curiosity rather than a beauty. So Tobias's parents had him instead. I can see where he got his looks. I bounced over to say hi." "And?"

"I think Tobias was relieved to escape from their argument. He gave me a kiss that practically froze our lips together, it was that cold out, and then he swung me around to meet this woman, saying, 'Claire, this is my mother, E/ena.' Imagine pronouncing your mother's name to someone like it was a joke. Such rudeness.

"Anyway, Elena was hardly the same woman who danced the samba carrying a pitcher of lemonade in Washington, D.C., long ago. She looked like she'd been heavily shrinkwrapped since then; I could sense a handful of pill vials chattering away in her handbag. The first thing she says to me is 'My, how healthy you look. So tanned.' Not even a hello. She had a civil enough manner, but I think she was using her talking-to-a-shop-clerk voice.

"When I told Tobias that the restaurant we were going to go to was closed, she offered to take us up to 'her restaurant' for lunch uptown. I thought that was sweet, but Tobias was hesitant, not that it mattered, since Elena overrode him. I don't think he ever lets his mother see the people in his life, and she was just curious.

"So off we went to Broadway, the two of them toasty warm in their furs (Tobias was wearing a fur—what a dink.) while me and my bones were clattering away in mere quilted cotton. Elena was telling me about her art collection ('I live for art') while we were toddling through this broken backdrop of carbonized buildings that smelled salty-fishy like caviar, grown men with ponytails wearing Kenzo, and mentally ill homeless people with AIDS being ignored by just about everybody."

"What restaurant did you go to?"

"We cabbed. I forget the name: up in the east sixties. Trop chic, though. Everything is très trop chic these days: lace and candles and dwarf forced narcissi and cut glass. It smelled lovely, like powdered sugar, and they simply fawned over Elena. We got a banquette booth, and the menus were written in chalk on an easeled board, the way I like because it makes the space so cozy. But what was curious was the way the waiter faced the menu board only toward me and Tobias. But when I went to move it, Tobias said, 'Don't bother. Elena's allergic to all known food groups. The only thing she eats here is seasoned millet and rainwater they bring down from Vermont in a zinc can.'

"I laughed at this but stopped really quickly when Elena made a face that told me this was, in fact, correct. Then the waiter came to tell her she had a phone call and she disappeared for the whole meal.

"Oh—for what it's worth, Tobias says hello," Claire says, lighting another cigarette.

"Gee. How thoughtful."

"Alright, alright. Sarcasm noted. It may be one in the morning here, but I'm not missing things yet. Where was I? Right—Tobias and I are alone for the first time. So do I ask him what's on my mind? About why he ditched me in Palm Springs or where our relationship is going? Of course not. I sat there and babbled and ate the food, which, I must say, was truly delicious: a celery root salad remoulade and John Dory fish in Pernod sauce. Yum.

"The meal actually went quickly. Before I knew it, Elena returned and zoom: we're out of the restaurant, zoom: I got a peck-peck on the cheeks, and then zoom: she was in a cab off toward Lexington Avenue. No wonder Tobias is so rude. Look at his training.

"So we were out on the curb and there was a vacuum of activity. I think the last thing either of us wanted then was to talk. We drifted up Fifth Avenue to the Met, which was lovely and warm inside, all full

|

of museum echoes and well-dressed children. But Tobias had to wreck whatever mood there may have been when he made this great big scene at the coat check stand, telling the poor woman there to put his coat out back so the animal rights activists couldn't splat it with a paint bomb. After that we slipped into the Egyptian statue area. God, those people were teeny weeny.

"Am I talking too long?" "No. It's Armand's money, anyway."

"Okay. The point of all this is that finally, in front of the Coptic pottery shards, with the two of us just feeling so futile pretending there was something between us when we both knew there was nothing, he decided to tell me what's on his mind—Andy, hang on a second. I'm starving. Let me go raid the fridge."

"Right now? This is the best part—" But Claire has plonked down the receiver. I take advantage of her disappearance to remove my travel-rumpled jacket and to pour a glass of water, allowing the water in the tap to run for fifteen seconds to displace the stale water in the pipes. I then turn on a lamp and sit comfortably in a sofa with my legs on the ottoman. "I'm back," says Claire, "with some lovely cheesecake. Are you going to help Dag tend bar at Bunny Hollander's party tomorrow night?" (What party?) "What party?"

"I guess Dag hasn't told you yet."

"Claire, what did Tobias say?"

I hear her take in a breath. "He told me part of the truth, at least.

He said he knew the only reason I liked him was for his looks and that

there was no point in my denying it. (Not that I tried.) He said he knows

that his looks are the only thing lovable about him and so that he might

as well use them. Isn't that sad?"

I mumble agreement, but I think about what Dag had said last week, that Tobias had some other, questionable reason for seeing Claire—for crossing mountains when he could have had anyone. That, to me, is a more important confession. Claire reads my mind:

"But the using wasn't just one way. He said that my main attraction for him was his conviction that I knew a secret about life—some magic insight I had that gave me the strength to quit everyday existence. He said he was curious about the lives you, Dag, and I have built here on the fringe out in California. And he wanted to get my secret for

himself—for an escape he hoped to make—except that he realized by listening to us talk that there was no way he'd ever really do it. He'd never have the guts to live up to complete freedom. The lack of rules would terrify him. / don't know. It sounded like unconvincing horseshit to me. It sounded a bit too pat, like he'd been coached. Would you believe it?"

Of course I wouldn't believe a word of it, but I abstain from giving an opinion. "I'll stay out of that. But at least it ended cleanly—no messy afterbirth..."

"Cleanly? Hey, as we were leaving the gallery and heading up Fifth Avenue, we even did the let's-still-be-friends thing. Talk about pain free. But it was when we were both walking and freezing and thinking of how we'd both gotten off the hook so easily that I found the stick.

"It was a Y-shaped tree branch that the parks people had dropped from a truck. Perfectly shaped like a water dowsing rod. Well! Talk about an object speaking to you from beyond! It just woke me up, and never in my life have I lunged so instinctively for an object as though it were intrinsically a part of me—like a leg or an arm I'd casually misplaced for twenty-seven years.

"I lurched forward, picked it up in my hands, rubbed it gently, getting bark scrapes on my black leather gloves, then grabbed onto both sides of the forks and rotated my hands inward—the classic water dows-er's pose.

"Tobias said, 'What are you doing? Put that down, you're embar-rassing me,' just as you'd expect, but I held right on to it, all the way down Fifth to Elena's in the fifties, where we were going for coffee.

"Elena's turned out to be this huge thirties Moderne co-op, white everything, with pop explosion paintings, evil little lap dogs, and a maid scratching lottery tickets in the kitchen. The whole trip. His family sure has extreme taste.

"But I could tell as we were coming through the door that the rich food from lunch and the late night before was catching up with me. Tobias went to make a phone call in a back room while I took my jacket and shoes off and lay down on a couch to veg-out and watch the sun fade behind the Lipstick Building. It was like instant annihilation—that instant fuzzy bumble-bee anxiety-free afternoony exhaustion that you never get at night. Before I could even analyze it, I turned into furniture.

"I must have been asleep for hours. When I woke it was dark out

and the temperature had gone down. There was an Arapaho blanket on top of me and the glass table was covered with junk that wasn't there before: potato chip bags, magazines.... But none of it made any sense to me. You know how sometimes after an afternoon nap you wake up with the shakes or anxiety? That's what happened to me. I couldn't remember who I was or where I was or what time of year it was or anything. All I knew was that / was. I felt so wide open, so vulnerable, like a great big field that's just been harvested. So when Tobias came out from the kitchen, saying, 'Hello, Rumplestiltskin,' I had a flash of remembrance and I was so relieved that I started to bellow. Tobias came over to me and said, 'Hey what's the matter? Don't cry on the fabric... come here, baby." But I just grabbed his arm and hyperventilated. I think it confused him.

"After a minute of this, I calmed down, blew my nose on a paper towel that was lying on the coffee table, and then reached for my dowsing branch and held it to my chest. Tobias said, 'Oh, God, you're not going to fixate on the twig again, are you? Look, I really didn't realize a breakup would affect you so much. Sorry.'

' 'Excuse me?' I say. 'I can quite deal with our breakup, thank you. Don't flatter yourself. I'm thinking of other things.' " 'Like what?'

' 'Like I finally know for sure who I'm going to fall in love with. The news came to me while I was sleeping.' '' 'Share it with me Claire.'

' 'Possibly you'll understand this, Tobias. When I get back to California, I'm going to take this stick and head out in the desert. I'm going to spend every second of my free time out there—dowsing for water buried deep. I'm going to bake in the heat and walk for miles and miles across the nothingness—maybe see a roadrunner and maybe get bitten by a rattler or a sidewinder. And one day, I don't know when, I'm going to come over a sand dune and I'll find someone else out there dowsing for water, too. And I don't know who that someone will be, but that's who I'm going to fall in love with. Someone who's dowsing for water, just like me.'

"I reached for a bag of potato chips on the table. Tobias says to me, 'That's really great, Claire. Be sure you wear hot pants and no panties and maybe you can hitchhike and you can have biker-sex in vans with strange men.'

|

"But I ignored his comment, and then, as I was reaching for a potato chip there on the glass table, I found behind the bag a bottle of Honolulu Choo-Choo nail polish.

"Well.

"Tobias saw me pick it up and stare at the label. He smiled as my mind went blank and then was replaced by this horrible feeling—like something from one of Dag's horror stories where a character is driving along in a Chrysler K-Car and then the character suddenly realizes there's a murderous drifter hidden behind the bench seat holding a piece of rope.

"I grabbed for my shoes and started to put them on. Then my jacket. I curtly said it was time I got going. That's when Tobias started lashing into me with this slow growly voice. 'You're just so sublime, aren't you, Claire. Looking for your delicate little insights with your hothouse freak show buddies out in Hell-with-Palm-Trees, aren't you? Well I'll tell you something, I like my job here in the city. I like the hours and the mind games and the battling for money and status tokens, even though you think I'm sick for wanting any part of it.'

"But I was already heading for the door; passing by the kitchen I saw briefly, but clearly enough, two milk-white crossed legs and a puff of cigarette smoke, all cropped by a door frame. Tobias was close on my heels as he followed me out into the hallway and toward the elevators. He kept going, he said, 'You know, when I first met you, Claire, I thought that here might finally be a chance for me to be a class-act for once. To develop something sublime about myself. Well fuck sublime, Claire. I don't want dainty little moments of insight. I want everything and I want it now. I want to be ice-picked on the head by a herd of angry cheerleaders, Claire. Angry cheerleaders on drugs. You don't get that, do you?'

"I had pushed the elevator button and was staring at the doors, which couldn't seem to open soon enough. He kicked away one of the dogs that had followed us, continuing his tirade.

" 'I want action. I want to be radiator steam hissing on the cement of the Santa Monica freeway after a thousand-car pile up—with acid rock from the smashed cars roaring in the background. I want to be the man in the black hood who switches on the air raid sirens. I want to be naked and windburned and riding the lead missile of a herd heading over to bomb every little fucking village in New Zealand.'

"Fortunately, the door finally opened. I got inside and looked at Tobias without saying anything. He was still aiming and firing: 'Just go to hell, Claire. You and your superior attitude. We're all lapdogs; I just happen to know who's petting me. But hey— if more people like you choose not to play the game, it's easier for people like me to win.'

"The door closed and I just waved good-bye, and when 1 began descending, I was shaking a bit—but the backseat drifter was gone. I was released from the obsession, and before I'd reached the lobby I couldn't believe what a brain-dead glutton I'd been—for sex, for humiliation, for pseudodrama.... And I planned right there never to repeat this sort of experience ever again. The only way you can deal with the Tobiases of this world is to not let them into your lives at all. Blind yourself to their wares. God, I felt relieved; not the least bit angry."

We both consider her words.

"Eat some of your cheesecake, Claire. I need time to digest all this."

"Naah. I can't eat; I've lost my appetite. What a day. Oh, by the way, could you do a favor for me? Could you put some flowers in a vase for me in my place for when I get back tomorrow? Some tulips, maybe? I'm going to need them."

"Oh. Does this mean you'll be back living in your old bungalow

again?"

"Yes."

Today is a day of profound meteorologic interest. Dust tornadoes have

struck the hills of Thunderbird Cove down the valley where the Fords

live; all desert cities are on a flash-flood alert. In Rancho Mirage, an

oleander hedge has made a poor sieve and has allowed a prickly mist

of tumbleweed, palm skirting, and desiccated empty tubs of Big Gulp

slush drink to pelt the wall of the Barbara Sinatra Children's Center.

Yet the air is warm and the sun contradictorily shines. "Welcome

back, Andy," calls Dag. "This is what weather

was like back in the six- ties." He's waist deep in

the swimming pool, skim- ming the water's surface

with a net. "Just look at the big big sky up

there. And guess what— while you were away

the landlord cheaped-out and bought a secondhand

cover sheet for the pool. Look at what happened—"

IWhat happened, was that the sheet of bubble-wrap covering, after years of sunlight and dissolved granulated swimming pool chlorine, has reached a critical point; the covering's resins have begun to disintegrate, releasing into the water thousands of delicate, fluttery plastic petal blossoms that had previously encased air bubbles. The curious dogs, their golden paws going clack-clack on the pool's cement edge, peek into the water, sniffing but not drinking, and they briefly inspect Dag's legs,

the list. It'll be fun. That's assuming, of course, that the winds today don't blow all of our houses to bits. Jesus, listen to them."

"So, Dag, what about the Skipper?"

"What about him?"

"Think he'll narc on you?"

"If he does, I'll deny it. You'll deny it, too. Two versus one. I'm not into being prosecuted for felonies."

The thought of anything legal or prison oriented petrifies me. Dag can read this on my face: "Don't sweat it, sport. It'll never come to that. I promise. And guess what. You won't believe whose car it was..."

"Whose?"

"Bunny Hollander's. The guy whose party we're catering tonight."

"Oh, Lord."

T H E T E N S: The first decade of a new century.

*****

Fickle dove-gray klieg light spots twitch and dart underneath tonight's overcast clouds, like the recently released contents of Pandora's box.

I'm in Las Palmas, behind the elaborate wet bar of Bunny Hollander's sequin-enhanced New Year's gala. Nouveaux riches faces are pushing themselves into mine, simultaneously bullying me for drinks (parvenu wealth always treats the help like dirt) and seeking my approval—and possibly my sexual favor.

It's a B-list crowd: TV money versus film money; too much attention given to bodies too late in life. Better looking but a bit too flash; the deceiving pseudohealth of sunburned fat people; the facial anonymity found only among babies, the elderly, and the overly face-lifted. There is a hint of celebrities, but none are actually present; too much money and not enough famous people can be a deadly mix. And while the party most definitely roars, the lack of famed mortals vexes the host, Bunny Hollander.

Bunny is a local celebrity. He produced a hit Broadway show in 1956, Kiss Me, Mirror or some such nonsense, and has been coasting on it for almost thirty-five years. He has glossy gray hair, like a newspaper left out in the rain, and a permanent leer that makes him resemble a child molester, the result of chain face-lifts since the nineteen sixties. But then Bunny knows lots of disgusting jokes and he treats staff well —the best combo going—so that makes up for his defects.

METAPHASIA: An inability to perceive metaphor.

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2014-12-23; Просмотров: 493; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!