КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

NOTATION. What is the best suitable way of representing intonation in the text?

|

|

|

|

What is the best suitable way of representing intonation in the text?

There are a variety of methods for recording intonation patterns in writing and we can look at the advantages and disadvantages of some of the commoner ones. The first three methods

reflect variations in pitch only:

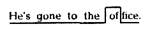

1. The method introduced by Ch. Fries (56) involves drawing a line around the sentence to show relative pitch heights:

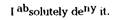

2. According to the second method the syllables are written at different heights across the page. The method is particularly favoured by D.Bolinger (47), for example:

Bolinger's book of reading has the cover title:

This method is quite inconvenient as its application wants a special model of print.

3. According to the third, "levels" method, a number of dis crete levels of pitch are recognized, and the utterance is marked accordingly. This method was favoured by some American linguists such as K.Pike (71) and others who recognized four levels of pitch, low, normal, high and extra-high, numbering them from 1—4. Since most linguists who have adopted this method have favoured low-to-high numbering, we shall use this in our example:

He's gone to the 3o'ffice.

This notation corresponds to the pattern of the example illustrating the first method.

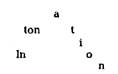

4. The fourth method is favoured by most of the British phoneticians such as D.Jones, R.Kingdon, J.D.O'Connor and G.F.Arnold, M.Halliday, D.Crystal and others, as well as by Soviet phoneticians who have successfully developed and improved it. This method has a number of advantages. Firstly, not only variations of pitch but also stressed syllables are marked. Secondly, distinct modifications of pitch in the nuclear syllable are indicated by special symbols, i.e. by a downward and an up ward arrow or a slantwise stress mark. More than that. Pitch movements in the pre-nuclear part can be indicated too. Thirdly, it is very convenient for marking intonation in texts.

One of the disadvantages of this method is that there has been no general agreement about the number of terminal tones and pre-nuclear parts English intonation system requires in order to provide an adequate description. So the simplest (D.Jones) recognizes only two tones, a fall and a rise — easy to distinguish, but not sufficient for the phonological analysis. We should definitely give preference to a more complex system, such as J.D.O'Connor and G.F.Arnold's, which has no fewer than ten different nuclear tones. It is quite sufficient for teaching pronunciation even to high-levelled learners. The most detailed indication of the pre-nuclear part of the intonation pattern is introduced in the textbook "Практическая фонетика английского языка" (28) in which J.D.O'Connor and G.F.Arnold's system has undergone further modification. All the relevant pitch changes in the pre-nuclear part are indicated by arrows placed before the first stressed syllable instead of an ordinary stress-mark, cf.:

That 'isn't as 'simple as That ~*isn't as 'simple as it

it ^sounds. 'sounds.

That isn't as 'simple as it

'sounds.

That.isn't as 'simple as it

'sounds.

We believe it is clear from the above that this system deserves recognition not only because it reflects all relevant variations of the two prosodic components of intonation but also because it serves a powerful visual aid for teaching pronunciation.

Our further point will be the description of intonation in the functional level. The problem that has long ago been with us becomes more pressing — how to capture in a meaningful and useful summary, just what intonation contributes. How can teachers and learners get a working grasp of its significance? And, finally, what is a typical use of intonation in a language like English?

Intonation is a powerful means of human intercommunication. So we shall consider the communicative function the main function of intonation. One of the aims of communication is the exchange of information between people. The meaning of an English utterance, i.e. the information it conveys to a listener, derives not only from the grammatical structure, the lexical composition and the sound pattern. It also derives from variations of intonation, i.e. of its prosodic parameters.

The communicative function of intonation is realized in various ways which can be grouped under five general headings. Intonation serves:

1) To structure the information content of a textual unit so as to show which information is new or cannot be taken for granted, as against information which the listener is assumed to possess or

to be able to acquire from the context, that is given information.

2) To determine the speech function of a phrase, i.e. to indicate whether it is intended as a statement, question, command, etc.

3) To convey connotational meanings of "attitude" such assurprise, annoyance, enthusiasm, involvement, etc. This can include whether meaning are intended, over and above the meanings conveyed by the lexical items and the grammatical structure. For example, the sentence: 'Thanks for helping me last night" can be given more than one meaning. The difference between a sincere intention and a sarcastic one would be conveyed by the intonation. Note that in the written form, we are given only the lexics and the grammar. The written medium has very limited resources for marking intonation, and the meanings conveyed by it have to be shown, if at all, in other ways.

4 To structure a text. As you know, we hope, intonation is an organizing mechanism. On the one hand, it delimitates texts into smaller units, i.e. phonetic passages, phrases and intonation groups, on the other hand, it integrates these smaller constituents forming a complete text.

1. To differentiate the meaning of textual units (i.e. intonation groups, phrases and sometimes phonetic passages) of the

same grammatical structure and the same lexical composition, which is the distinctive or phonological function of intonation.

2. To characterize a particular style or variety of oral speech which may be called the stylistic function.

There is no general agreement about either the number or the headings of the functions of intonation which can be illus trated by the difference in the approach to the subject by some prominent Soviet phoneticians. T.M.Nikolajeva names the three functions of intonation: delimitating, integrating and semantic functions (24). L.KTseplitis suggests the semantic, syntactic and stylistic functions the former being the primary and the two latter being the secondary functions (35); N.V.Cheremisina singles out the following main functions of intonation: communicative, distinctive (or phonological), delimitating, expressive, appellative, aesthetic, integrating (36). Other Soviet and foreign phoneticians also display some difference in heading the linguistic functions of intonation.

Summarizing we may say that intonation is a powerful means of communication process. It follows from this that it is definitely not possible to divorce any function of intonation from that of communication. No matter how many functions are named, all of them may be summed up under a more general heading, that is the function of communication. It should be pointed out here that the structuring functions of intonation mentioned above (delimitating and integrating functions) should be viewed alongside with other functions serving the purpose of communication.

The descriptions of intonation show that phonological facts of intonation system are much more open to question than in the field of segmental phonology. Descriptions differ according to the kind of meaning they regard intonation is carrying and also according to the significance they attach to different parts of the tone-unit. J.D.O'Connor and G.F.Arnold assert that a major function of intonation is to express the speaker's attitude to the situation he is placed in, and they attach these meanings not to pre-head, head and nucleus separately, but to each of ten "tone-unit types" as they combine with each of four sentence types, statement, question, command and exclamation.

M.Halliday supposes that English intonation contrasts are grammatical. He argues first that there is a neutral or unmarked tone choice and then explains all other choices as meaningful by contrast (59). Thus if one takes the statement "I don't know" the suggested intonational meanings are:

Low Fall — neutral

Low Rise — non-committal

High Rise — contradictory

Fall-Rise — with reservation

Rise-Fall — with commitment

Unlike J.D.O'Connor and G.F.Arnold, M.Halliday attributes separate significance to the pre-nuclear choices, again taking one choice as neutral and the other(s) as meaningful by contrast.

D.Crystal presents an approach based on the view "that any explanation of intonational meaning cannot be arrived at by seeing the issues solely in either grammatical or attitudinal terms". He ignores the significance of рге-head and head choices and deals only with terminal tones. He supports R. Quirk's view that a tone unit has a falling nucleus unless there is some specific reason why it should not and illustrates this statement by observing that non-final structures are marked as such by the choice of low- or mid-rising or level tones (50).

There are other similar approaches which possess one feature in common: all of them pay little attention to the phonological significance of pitch level and pitch range.

The approach we outline in this book is different again. On the phonological level intonation is viewed as a complex structure of all its prosodic parameters. We see the description of intonation structure as one aspect of the description of interaction and argue that intonation choices carry information about the structure of the interaction, the relationship between and the discourse function of individual utterances, the international "given-ness" and "newness" of information and the state of convergence and divergence of the participants.

Now we shall have a brief outlook on how intonation functions as a means of communication. One of the functions of intonation is too structure the information content of an intonation group or a phrase so as to show which information is new, as against information which the listener is assumed to possess or to be able to acquire from the context.

In oral English the smallest piece of information is associated with an intonation group, that is a unit of intonation containing the nucleus.

There is no exact match between punctuation in writing and intonation groups in speech. Speech is more variable in its structuring of information than writing. Cutting up speech into intonation groups depends on such things as the speed at which you 'are speaking, what emphasis you want to give to the parts of the message, and the length of grammatical units. A single phrase may have just one intonation group; but when the length of phrase goes beyond a certain point (say roughly ten words), it is difficult not to split it into two or more separate pieces of information, e.g.

The man told us we could park it here.

The man told us | we could park it at the railway station.

The man told us | we could park it | in the street over there.

Accentual systems involve more than singling out important words by accenting them. Intonation group or phrase accentuation focuses on the nucleus of these intonation units. The nucleus marks the focus of information or the part of the pattern to which the speaker especially draws the hearer's attention The focus of information may be concentrated on a single word or spread over a group of words.

Out of the possible positions of the nucleus in an intonation group, there is one position which is normal or unmarked, while the other positions give a special or marked effect. In the example: "He's gone to the office" the nucleus in an unmarked position would occur on "office". The general rule is that, in the unmarked case, the nucleus falls on the last lexical item of the intonation group and is called the end-focus. In this case sentence stress is normal.

But there are cases when you may shift the nucleus to an earlier part of the intonation group. It happens when you want to draw attention to an earlier part of the intonation group, usually to contrast it with something already mentioned, or understood in the context. In the marked position we call the nucleus contrastive focus or logical sentence stress. Here are some examples:

"Did your brother study in Moscow?" "vNo, $ he was,born in Moscow."

In this example contrastive meaning is signalled by the falling tone and the increase of loudness on the word "born".

Sometimes there may be a double contrast in the phrase, each contrast indicated by its own nucleus:

Her ^mother | is vRussian | but her vfather | is, German.

In a marked position, the nuclei may be on any word in an intonation group or a phrase. Even words like personal pronouns, prepositions and auxiliaries, which are not normally stressed at all, can receive nuclear stress for special contrastive purposes:

It's not 4her book, | it's xours.

Which syllable of the word is stressed if it has more than one syllable, is determined by ordinary conventions of word stress: to'morrow, 'picture,,demons'tration.

In exceptional cases, contrastive stress in a word of more than one syllable may shift to a syllable which does not normally have word stress. For example, if you want to make a contrast between" the two words normally pronounced bu'reaucracy and autocracy you may do so as follows: 'bureaucracy and'autocracy.

The widening of the range of pitch of the nucleus, the increase of the degree of loudness of the syllable, the slowing down of the tempo make sentence accent emphatic:

A. ~*Tom has ^passed his exam.

B. Well vfancy Htiat!

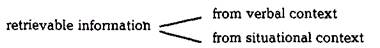

We can roughly divide the information in a message into given, or retrievable information (or the theme) and new infor mation (or the rneme). Given information is something which the speaker assumes the hearer knows about already. New information can be regarded as something which the speaker does not assume the hearer knows about already. Here is an example;

A. What did John say to you?

B. He was ~*talking to vMary | not to xme.

In the response "He was talking" is given information; it is already given by the preceding clause; "not to me" conveys new information. A new information is obviously what is most important in a message, it receives the information focus, in the nucleus, whereas old information does not.

Given information suggests information which has already been mentioned or alluded to. But this notion may be extended by- including information which is given by the situation outside language. For example, if a few different persons are expected to come, the phrase "The doctor has come" is pronounced' with the nucleus on the word "doctor" though no speech context •preceded it.

By putting the stress on one particular word, the speaker shows, first, that he is treating that word as the carrier of new, non-retrievable infonnation, and, second, that the information of the other, non-emphasized, words in the intonation group is not new but can be retrieved from the context. "Context" here is to be taken in a very broad sense: it may include something that has already been said, in which case the antecedents may be very specific, but it may include only something (or someone) present in the situation, and it may even refer, very vaguely, to some aspect of shared knowledge which the addressee is thought to be aware of. The information that the listener needs in order to interpret the sentence may therefore be retrievable either from something already mentioned, or from the general "context of situation":

Notice that the decision as to whether some information is retrievable or not has to be made by the speaker on the basis of what he thinks the addressee can take for granted from the situation, etc., The speaker must, in framing the utterance, make many assumptions, and he does this rapidly and to a large degree unconsciously. He then arranges his intonation groups and assigns nuclear stresses accordingly. But in any particular situation, the speaker's assumptions run the risk of being wrong; what he takes to be retrievable information may not in fact be retrievable for the addressee. In this case there is a breakdown of communication, and the listener will probably seek clarification:

(A. and B. are passing the tennis courts)

A. There isn't anyone playing.

B. Who said there was?

A. Nobody.

Dialogues like this, though not uncommon, are unsatisfactory because vital information is missing. By putting the nucleus on "isn't" speaker A took "anyone playing" as retrievable information. В responds with a request for an explanation, which A then fails to fulfil. If A had put the original nucleus on "playing", the conversation could have proceeded normally.

Degrees of information are relevant not only to the position of sentence stress but also to the choice of the nuclear tone. We' tend to use a falling tone of wide range of pitch combined with a greater degree of loudness, that is emphatic stress, to give emphasis to the main information in a phrase. To give subsidiary or less important information, i.e. information which is more predictable from the context or situation, the rising or level nuclear tone is used, e.g

A. I saw your sister at the game yesterday.

main subsidiary

B. Yes, watching tennis is her favourite.pastime.

subsidiary main

The English language is not only a means of giving and receiving information. As was stated above, it is more than this: it is communication between people. It commonly expresses the attitudes and emotions of the speaker and he often uses it to influence the attitudes and behaviour of the hearer. This function of intonation makes it "the salt of an utterance. Without it a statement can often be understood, but the message is tasteless, colourless. Incorrect uses of it can lead to embarrassing ambiguities" (55).

So another use of intonation in English is that of transmitting feelings or emotions and modality. But it is fair to note here that language has to be conventional, it has more important business than transmitting feelings, and this forces it to harness emotion in the service of meaning.

As with words which may have two or more related lexical meanings so with intonation patterns one must indicate a central meaning with marginal variations from it. In English meanings of intonation patterns are largely of this general type. Most phrases and parts of them may be pronounced with several different intonation patterns according to the situation, according to the speaker's momentary feeling or attitude to the subject matter. These modifications can vary from surprise to deliberation, to sharp isolation of some part of a sentence for attention, to mild intellectual detachment. It would not be wise to associate a particular intonation pattern with a particular grammatical construction. Any sentence in various contexts may receive any of a dozen other patterns, cf.:

When can you do it? — xNow. (detached, reserved)

When did you finish? — xNow. (involved)

When did you come? —.Now. (encouraging further conversation)

You are to do it right now. — ^ow? (greatly astonished)

We have so far confined our description to the significance of intonation within phrases; we now want to discuss the function of intonation with reference to the model of discourse structure, i.e. to handle the way in which functional units combine together.

In recent years some promising attempts have been made to describe intonation with reference to structures of discourse, rather than to grammatical categories. By discourse is meant a sequence of utterances, usually involving exchanges between two or more participants, though monologue is not excluded from this definition.

Probably the most important grammatical function of intonation in the language family to which English belongs is that of tying the major parts together within the phrase and tying phrases together within the text — showing, in the process, what things belong more closely together than others, where the divisions come, what is subordinate to what, and whether one is telling, asking, commanding or exclaiming.

In other words, in previous sections we have considered aspects of meaning in isolation, but now we shall be thinking about how meanings may be put together and presented in an oral discourse. We shall start with the organization of connections between phrases, with considering how one idea leads on from another. Intonation is one of the means that fulfil this connection or integrating function.

A phrase usually occurs among other phrases; it is, in fact, usually connected to them in some way. A phrase is most closely connected to its context phrases, which is often the one just preceding it. It is useful to say that a phrase is a response to its context and is relevant to that context. These notions can be illustrated with the following two-line dialogue:

A. Where is John?

B. He is in-the house.

In this dialogue phrase Л is the context for phrase B. Conversely, В is a response to A and is relevant to A. This particular relevance may be called "answer to a special question". Relevance is the phenomenon that permits humans to converse. It is clear that if we treat a phrase like В in isolation, with their contexts shipped away, relevance evaporates. That fact alone is a powerful argument for the propriety of dealing with phrases in context, for without context there is no relevance. But an even more powerful argument is this: a context phrase acts as a floodlight upon the response, revealing details about the response, and clarifying its structure and meaning. If we remove a phrase from its context we shut off that light. The very facts that we are trying to understand may be obscured. Some illustrations will show what is meant.

If we take an utterance like "John" we cannot discern much about its structure or meaning. But the moment we make it relevant to a context, the structure and meaning leap into focus, as in the following:

Who is in the house? John.

Instantly the observer sees that the response is elliptical and that it has the underlying structure "John is in the house". It is the context that allows this interpretation. But the very same phonetic sequence "John", if taken in a different context, is revealed to have a completely different structure and meaning, as in the following:

Who did they see? John.

The full form of the response is "They saw John", a phrase in which the sequence "John" is now the object. Thus two examples of the utterance "John" appear to be identical if taken in isolation, but different contexts allow us to see them as fundamentally different.

One and the same word sequence may be pronounced with different intonation being relevant to different contexts, e.g.

A. Did ~*John phone you yesterday? _»Did.John phone

you yesterday?

B. xNo, Tom. ^No, \ xTom.

Not only the use of particular pitch changes is an important means of tying intonation groups or phrases together.

Accents and particular positions of accents seem to be characteristic of the phrase or of the text structure. We tend to favour the two extremes of the phrase, the beginning and the end, or, in longer phrases, the two extremes in an intonation group as if to announce the beginning and the end. There may be intermediate accents, but they are less prominent:

The ~*snow °generally °comes in November.

Here the first strong accent is on "snow" and the last is on "November".

Similarly there is a tendency to arrange complete parts of the text when the opening and the closing phonetic passages are more prominent than the intermediate ones thus integrating parts into a whole text, e.g.

A gentleman was much surprised when a good-looking young lady greeted him by saying "Good evening". He couldn't remember ever seeing her before.

She evidently realized that she had made a mistake, for she apologized, and explained: "Oh, I am sorry. When I first saw you I thought you were the father of my two children." She walked on while the man stared after her. She didn't realize, of course, that he was unaware of the fact that she was a school teacher.

The pitch range, the degree of loudness of the first and the last phonetic passages are comparatively higher and the tempo is definitely slower as compared to the second phonetic whole. These are just some examples of how intonation is involved in the text-structuring process which forms a good evidence of its integrating ability.

Many linguists in this country and abroad attempt to view intonation on the phonological level. Phonology has a special branch, intonology, whose domain is the larger units of connected speech: intonation groups, phrases and even phonetic passages or blocks of discourse.

It is still impossible to classify, in any practical analysis of intonation, all the fine shades of feeling and attitude which can be conveyed by slight changes in pitch, by lengthening or shortening tones, by increasing or decreasing the loudness of the voice, by changing its quality, and in various other ways. On the other hand it is quite possible to make a broad classification of intonation patterns which are so different in their nature that they materially change the meaning of the utterance to which they are applied, and to make different pitches and degrees of loudness in each of them. Such an analysis resembles the phonetic analysis of sounds of a language whereby phoneticians establish the number of significant sounds it uses. Applied to intonation it can be of the greatest service in guiding students in the correct use of the tones and accents they are learning.

The distinctive function of intonation is realized in the opposition of the same word sequences which differ in certain parameters of the intonation pattern.

Intonation patterns make their distinctive contribution at intonation group, phrase and text levels. Thus in the phrases:

If vMary.comes \ let me -»know If -»Mary.comes \ let me

at vonce. (a few people are -»know at vonce. (no one

expected to come but it is else but Mary is expected

Mary who interests the speaker) to come)

the intonation patterns of the first intonation groups are opposed.

In the opposition "I enjoyed it" — "I enjoyed,it" the pitch pattern operates over the whole phrase adding in the second phrase the notion that the speaker has reservations (implying a continuation something like "but it could have been a lot better").

In the dialogue segments which represent text units

A. You must a-»pologize at xonce. You must avpologize at

once.

B. I f don't 'see why I vshould. I _»don't.see why I

.should.

the opposition of intonation patterns of both the stimulus and the response manifests different meaning.

Any section of the intonation pattern, any of its three constituents can perform the distinctive function thus being phonological units. These units form a complex system of intonemes, tonemes, accentemes, chronemes, etc. These phonological units like phonemes consist of a number of variants. The terminal tonemes, for instance, consist of a number of allotones, which are mutually non-distinctive. The principal allotone is realized in the nucleus alone. The subsidiary allotones are realized not only in the nucleus, but also in the pre-head and in the tail, if there are any, cf.:

xNo. ^No, Tom. Oh, xno, Mary.

The most powerful phonological unit is the terminal tone. The opposition of terminal tones distinguishes different types of sentence. The same sequence of words may be interpreted as a different syntactical type, i.e. a statement or a question, a question or an exclamation being pronounced with different terminal tones, e.g.

iTom saw it. Tom saw it?

(statement) (general question)

-»Didn' t you en joy it? "* Didn' t you en Joy it?

(general question) (exclamation)

Will you be,quiet? Will you be vquiet?

(request) (command)

The number of terminal tones indicates the number of intonation groups. Sometimes the number of intonation groups we choose to use may be important for meaning. For example, the sentence "My sister, who lives in the South, has just arrived" may mean two different things. In writing the difference may be marked by punctuation. In oral speech it is marked by using two or three intonation groups. If the meaning is: "My only sister who happens to live in the South...", then the division would be into three intonation groups: "My sister, | who lives in the South, \ has just arrived."

On the other hand, if the meaning is: "That one of my two sisters, who lives in the South", the division is into two intonation groups.

Other examples:

I didn't see the doctor | be- I didn't see the doctor

cause I was ill (and could because I was ill (but for

not go). some other reason for

example, to get my health card signed).

Thus, in one meaning the doctor was not seen, and in the other, he was.

Together with the increase of loudness terminal tones serve to single out the semantic centre' of the utterance. The words in an utterance do not necessarily all contribute an equal amount of information, some are more important to the meaning than others. This largely depends on the context or situation in which the intonation group or a phrase is said. Some words are predisposed by their function in the language to be stressed. In English, as you know, lexical (content) words are generally accented while grammatical (form) words are more likely to be unaccented although words belonging to both of these groups may be unaccented or accented if the meaning requires it.

Let us consider the sentence "It was an unusually rainy day." As the beginning of, say, a story told on the radio the last three words would be particularly important, they form the semantic centre with the nucleus on the word "day". The first three words play a minor part. The listener would get a pretty clear picture of the story's setting if the first three words were not heard because of some outside noise and the last three were heard clearly. If the last three words which form the semantic centre were lost there would be virtually no information gained at all.

The same sentences may be said in response to the question "What sort of day was it?" In this case the word "day" in the reply would lose some of its force because the questioner already possesses the information that it might otherwise have given him. In this situation there are only two important words — "unusually rainy" — and they would be sufficient as a complete answer to the question. The nucleus will be on the word "rainy". Going further still, in reply to the question "Did it rain yesterday?" the single word "unusually" would bear the major part of the information, would be, in this sense, more important than all the others and consequently would be the nucleus of the intonation pattern.

Grammatical words may be also important to the meaning if the context makes them so. The word "was", for instance, has had little value in the previous examples, but if the sentences were said as a contradiction in the reply to "It wasn't" a rainy day yesterday, was it?", then "was" would be the most important word of all and indeed, the reply might simply be "It was", omitting the following words as no longer worth saying. In this phrase the word "was" is the nucleus of the semantic centre.

These variations of the accentuation achieved by shifting the position of the terminal tone serve a striking example of how the opposition of the distribution of terminal tones is fulfilling the distinctive function.

There are exceptional cases when the opposition of terminal tones serves to differentiate the actual meaning of the sentence.

If the phrase "I don't want you to read anything" has the low-falling terminal tone on the word "anything", it means that for this or other reason the person should avoid reading. If the same word sequence is pronounced with the falling-rising tone on the same word, the phrase means that the person must have a careful choice in reading; or:

He's a -»French v teacher. He's a vFrench teacher.

(He comes from France.) (He teaches French.)

It should be pointed out here that the most important role of the opposition of terminal tones is that of differentiating the attitudes and emotions expressed by the speaker. The speaker must be particularly careful about the attitudes and emotions he expresses since the hearer is frequently more interested in the speaker's attitude or feeling than in his words — that is whether he speaks nicely or nastily.

The special question "Why?", for instance, may be pronounced with the low-falling tone sounding rather detached, sometimes even hostile. When pronounced with the low-rising tone it is sympathetic, friendly, interested.

Another example. The sentence "Yes" as a response to the stimulus "Did you agree with him?" pronounced with the low-falling tone sounds categoric, cool, detached. Being pronounced with the falling-rising tone, it implies quite a special shade of emotional meaning "up to the point", sounding concerned, hurt, tentatively suggesting.

All the other sections of the intonation pattern differentiate only attitudinal or emotional meaning, e.g.: being pronounced with the high pre-head, "Hello" sounds more friendly than when pronounced with the low pre-head, cf.:

-Hel.lo! - Hel.lo!

More commonly, however, different kinds of pre-heads, heads, the same as pitch ranges and levels fulfil their distinctive function not alone but in the combination with other prosodic constituents.

We have been concerned with the relationship between intonation, grammatical patterns and lexical composition. Usually the speaker's intonation is in balance with the words and structures he chooses. If he says something nice, his intonation usually reflects the same characteristic. All types of questions, for instance, express a certain amount of interest which is generally expressed in their grammatical structure and a special interrogative intonation. However, there are cases when intonation is in contradiction with the syntactic structure and the lexical content of the utterance neutralizing and compensating them, e.g.: a statement may sound questioning, interested. In this case intonation neutralizes its grammatical structure. It compensates the grammatical means of expressing this kind of meaning:

Do you know what I'm here for? —,No, (questioning)

There are cases when intonation neutralizes or compensates the lexical content of the utterance as it happens, for instance, in the command "-»Phone him at 4once, please", when the meaning of the word "please" is neutralized by intonation.

Lack of balance between intonation and word content, or intonation and the grammatical structure of the utterance may serve special speech effects. A highly forceful or exciting statement said with a very matter-of-fact intonation may, by its lack of balance, produce a type of irony; if one says something very complimentary, but with an intonation of contempt, the result is an insult.

There are cases when groups of intonation patterns may be treated as synonyms. It happens when fine shades of meaning in different situations modify the basic meaning they express, e.g.: the basic meaning of any falling tone in statements is finality. Low Fall and High Fall both expressing finality have their own particular semantic shades. Low Fall is used in. final, categoric detached statements. High Fall together with finality may express concern, involvement:

Where's my copy? - xPeter took it for you.

or: — vPeter took it for you.

Isn't it a lovely view? - De xlightful.

,or: -DeMightful.

Russian permits intonational patterns of a type not found in English. It offers many examples of quite specific constituents that is of the pre-nuclear and the nuclear parts. Intonation patterns in Russian are usually called "Intonation constructions" (интонационные конструкции abbreviated as "ИК"). There are five main intonation constructions and two occasional ones (i.e. emphatic variants). They are differentiated according to the type of the nucleus, the pitch direction on the pre-nuclear and post-nuclear syllables, the character of the word stress and the length, tenseness and quality of the stressed vowel in syllables bearing the nuclear tone.

The intonation constructions in the Russian language are associated with certain sentence types and the attitudinal meaning expressed by them is termed by the purpose of communication. We might state that the difference between English and Russian intonation lies both in structure and use.

Our next section will Ъе concerned with rhythmic structures of English which are formed by means of all prosodic components described in this section.

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2015-05-31; Просмотров: 2408; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!