КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

Introduction

|

|

|

|

FOREWORD

Chapter VI. Territorial Varieties of English Pronunciation

Functional Stylistics and Dialectology..........................

Spread of English..........................................................

English-Based Pronunciation Standards of English......

British English...........................................................

I. English English.......................................................

A. RP (Received Pronunciation)............................

Changes in the Standard..................................

B. Regional Non-RP Accents of England..............

II. Welsh English........................................................

III. Scottish English....................................................

IV. Northern Ireland English.....................................

American-Based Pronunciation Standards of English

American English..............................................

List of Works Consulted...............................................................

Phonetic structure of English is rather a vast area of study for teachers of this language. The purpose of our book is to describe the system of phonetic functional units and their use in the process of social communication.

The plan of this book is organized accordingly. Introduction makes some pleas for the value of phonetics for foreign language teaching and study, views phonetics as a branch of linguistics, establishes its connection with other fields of science, etc. Chapter I introduces the functional approach to the pronunciation of English in use. Chapter II is concerned with segmental phonemes. Chapters III, IV, V discuss supraseg-mental aspects including accentual structure, syllabic structure and intonation. Chapter VI is devoted to territorial varieties of English and its teaching norm.

The authors hope that during this course the students will be encouraged to enter into a dialogue with our book and savour the endless fascination of this aspect of linguistic organization.

This book is aimed at future teachers of English. The teachers of a foreign language are definitely aware of the existence of phonetics. They are always being told, that it is essential that they should be skilful phoneticians. The reaction may be different. Some teachers meet it with understanding. Some protest that it is not in their power, for various reasons, to become phoneticians, others deny that it is really necessary.

"Is it in fact necessary for a language teacher to be a phonetician? I would reply that all language teachers willy-nilly are phoneticians. It is not possible, for practical purposes, to teach a foreign language to any type of learner, for any purpose, by any method, without giving some attention to pronunciation. And any attention to pronunciation is phonetics" (42, p. 28).

What do we mean by phonetics as a science? Phonetics is concerned with the human noises by which the thought is actualized or given audible shape: the nature of these noises, their combinations, and their functions in relation to the meaning. Phonetics studies the sound system of the language, that is segmental phonemes, word stress, syllabic structure and intonation. It is primarily concerned with expression level. However, phonetics is obliged to take the content level into consideration too, because at any stage of the analysis, a considerable part of the phonetician's concern is with the effect which the expression unit he is examining and its different characteristics have on meaning. Only meaningful sound sequences are regarded as speech, and the science of phonetics, in principle at least, is concerned only with such sounds produced by a human vocal apparatus as are, or may be, carriers of organized information of language. Consequently, phonetics is important in the study of language. An understanding of it is a prerequisite to any adequate understanding of the structure or working of language. No kind of linguistic study can be made without constant consideration of the material on the expression level.

It follows from this, that phonetics is a basic branch — many would say the most fundamental branch — of linguistics; neither linguistic theory nor linguistic practice can do without phonetics, and no language description is complete without phonetics, the science concerned with the spoken medium of language. That is why phonetics claims to be of equal importance with grammar and lexicology.

Phonetics has two main divisions; on the one hand, phonology, the study of the sound patterns of languages, of how a spoken language functions as a "code", and on the other, the study of substance, that carries the code.

Before analysing the linguistic function of phonetic units we need to know how the vocal mechanism acts in producing oral speech and what methods are applied in investigating the material form of the language, that is its substance.

Human speech is the result of a highly complicated series of events. The formation of the concept takes place at a linguistic level, that is in the brain of the speaker; this stage may be called psychological. The message formed within the brain is transmitted along the nervous system to the speech organs. Therefore we may say that the human brain controls the behaviour of the articulating organs which effects in producing a particular pattern of speech sounds. This second stage may be called physiological. The movements of the speech apparatus disturb the air stream thus producing sound waves. Consequently the third stage may be called physical or acoustic. Further, any communication requires a listener, as well as a speaker. So the last stages are the reception of the sound waves by the listener's hearing physiological apparatus, the transmission of the spoken message through the nervous system to the brain and the linguistic interpretation of the information conveyed.

Although not a single one of the organs involved in the speech mechanism is used only for speaking we can, for practical purposes, use the term "oroans of speech" in the sense of the organs which are active, directly or indirectly, in the process of speech sound production.

In accordance with their linguistic function the organs of speech may be grouped as follows:

The respiratory or power mechanism furnishes the flow of air which is the first requisite for the production of speech sounds. This mechanism is formed by the lungs, the wind-pipe and the bronchi. The air-stream expelled from the lungs provides the most usual source of energy which is regulated by the power mechanism. Regulatmg the force of the air-wave the lungs produce variations in the intensity of speech sounds. Syllabic pulses and dynamic stress, both typical of English, с re directly related to the behavior of the muscles which activate this mechanism.

From the lungs through the wind-pipe their-stream passes to the upper stages of the vocal tract. First of all it passes to the larynx containing the vocal cords. The function of the vocal cords consists in their role as a vibrator set in motion by the air-stream sent by the lungs. At-least two actions of the vocal cords as a vibrator should be mentioned.

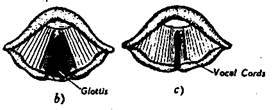

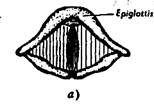

The opening between the vocal cords is known as the glottis. When the glottis is tightly closed and the air is sent up below it the so-called glottal stop is produced. It often occurs in English when it reinforces or even replaces [p], [t], or [k] or even when it precedes the energetic articulation of vowel sounds. The most important speech function of the vocal cords is their role in the production of voice. The effect of voice is achieved when the vocal cords are brought together and vibrate when subjected to the pressure of air passing from the lungs. This vibration is caused by compressed air forcing an opening of the glottis and the following reduced air-pressure permitting the vocal cords to come together again.

|

Glottal positions. Diagrams of some of the possible settings of the vocal cords:

a — tightly dosed as for the glottal stop; b — wide-open as for breath; с — loosely together and vibrating as for vfoice.

The height of the speaking voice depends on the frequency of the vibrations. The more frequently the vocal cords vibrate the higher the pitch is. The typical speaking voice of a man is higher than that of a woman because the vocal cords of a woman vibrate more frequently. We are able to vary the rate of the vibration thus producing modifications of the pitch component

of infonation. More than that. We are able to modify the size of the puff of air which escapes at each vibration of the vocal cords, that is we can alter the amplitude of the vibration which causes changes of the loudness of the sound heard by the listener.

From the larynx the air-stream passes to supraglottal cavities, that is to the pharynx, the mouth and the nasal cavities. The shapes of these cavities modify the note produced in the larynx thus giving rise to particular speech sounds.1

We shall confine ourselves here to a simple description of the linguistic function of the organs of speech, and refer the reader for further information to any standard handbook of anatomy and physiology, or, rather, to books on general linguistics.

There are three branches of phonetics each corresponding*to a different stage in the communication process mentioned above. Each of these branches uses quite special sets of methods.

The branch of phonetics that studies the way in which the air is set in motion, the movements of the speech organs and the coordination,of these movements in the production of single sounds and trains of sounds is called articulatory phonetics.

Acoustic phonetics studies the way in which the air vibrates between the speaker's mouth and the listener's ear. Until recently, articulatory phonetics has been the dominating branch, and most descriptive work has been done in articulatory terms. Furthermore, there has appeared no need to alter the balance in any substantial way, especially for the purpose of teaching, acoustic phonetics presenting special interest for research work and applied linguistics. Nevertheless, in the nearest future it may start to play a constantly growing part in teaching pronunciation. We may hope that the development of computing technique will give rise to all sort of teaching machines.

The branch of phonetics investigating the hearing process is known as auditory phonetics. Its interests lie more in the sensation of hearing, which is brain activity, than in the physiological working of the ear or the nervous activity between the ear and the brain. The means by which we discriminate sounds — quality, sensations of pitch, loudness, length, are relevant here. This branch of phonetics is of great interest to anyone who teaches or studies pronunciation.

It is interesting now to consider the methods applied in investigating the sound matter of the language.

It is useful to distinguish between phonetic studies carried out without other instruments of analysis than the human senses and-such as are based upon the witness of registering or computing machines and technical analysing or synthesizing devices. The use of such a device as the tape-recorder does not of course imply in itself any instrumental analysis of the speech recorded, but simply serves the purpose of facilitating the speech analysis and conserving a replica of the speech the informants use.

From the beginning of phonetics the phonetician has relied mainly on what he could feel of his own speech and on what he could hear both of his own and the informant's speech. By training and practice he gains a high degree of conscious control over the muscular functioning of his vocal apparatus, and by experience he may acquire considerable skill in associating the qualities of the heard sound with the nature of the articulations producing it. These skills are obligatory for phoneticians and make phonetics an art rather than a science, an art which must be specially learned.

Instrumental methods deriving from physiology and physics were introduced into phonetics in the second half of the last century in order to supplement and indeed to rectify the impressions deriving from the human senses, especially the auditory impressions; since these are affected by the limitations of the perceptual mechanism, and in general are rather subjective.

The use of instruments is valuable in ascertaining the nature of the limitations and characteristics of the human sensory apparatus by providing finer and more detailed analysis against which sensory analysis can be assessed. In a general way, the introduction of machines for measurements and for instrumental analysis into phonetics has resulted in their use for detailed study of many of the phenomena which are present in the sound wave or in the articulatory process at any given moment, and in the changes of these phenomena from moment to moment. This is strictly an instrumental method of study. This type of investigation together with sensory analysis is widely used in experimental phonetics.

The results available from instrumental analysis supplement those available from sensory analysis. Practically today there are no areas of phonetics in which useful work can and is being done without combining these two ways of phonetic investiga tion. The "subjective" methods of analysis by sensory impression and the "objective" methods of analysis by instruments are complementary and not oppositive to one another. Both "objective" and "subjective" methods are widely and justifiably used in modern phonetics. Articulatory phonetics borders with anatomy and physiology and the tools for investigating just what the speech organs do are tools which are used in these fields: direct observation, wherever it is possible, e.g. lip movement, some tongue movement; combined with x-ray photography or x-ray cinematography; observation through mirrors as in the laryngoscopic investigation of vocal cord movement, etc.

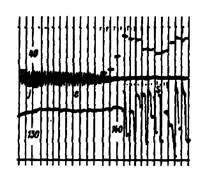

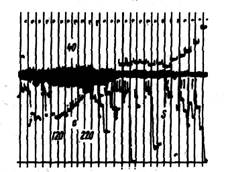

Acoustic phonetics comes close to studying physics and the tools used in this field enable the investigator to measure and analyse the movement of the air in the terms of acoustics. This generally means introducing a microphone into the speech chain, converting the air movement into corresponding electrical activity and analysing the result in terms of frequency of vibration and amplitude of vibration in relation to time. The use of such technical devices as spectrograph, intonograph and other sound analysing and sound synthesizing machines is generally combined with the method of direct observation.

The pictures on p. 11 may be a good illustration of the use of such a device as the intonograph.

The methods applied in auditory phonetics are those of experimental psychology.

As was stated above, phoneticians cannot act only as de-scribers and classifiers of the material form of phonetic units. They are also interested in the way in which sound phenomena function in a particular language, how they are utilized in that language and what part they play in manifesting the meaningful distinctions of the language. The branch of phonetics that studies the linguistic function of consonant and vowel sounds, syllabic structure, word accent and; prosodic features, such as pitch, stress and tempo is called phonology.

In linguistics, function Is usually understood to mean discriminatory function, that is, the role of the various elements of the language in the distinguishing of one sequence of sounds, such as a word or a sequence of words, from another of different meaning. Though we consider the discriminatory function to be the main linguistic function of any phonetic unit we cannot ignore the other function of phonetic units,.that is, their role in the formation of syllables, words, phrases and even texts. This functional^ ^эг social aspect of phonetic phenomena was first introduced in the woricsTvy I.A.Baudouin-de-Courtenay. Later on N.S.Trubetskoy declared phonology to be a linguistic science limiting articulatory and acoustic phonetics to anatomy, physiology and acoustics only. This conception is shared by many foreign linguists who investigate the material form and the function of oral speech units separately. Soviet linguists proceed from the truly materialistic view that language being the man's medium of thought can exist only in the material form of speech sounds. That is why they consider phonology a branch of phonetics that investigates its most important social_aspect. Phonology possesses its own methods of investigation which will be described later in the course

|

|

The intonogramme of the English phrases "Yes." "Yes?

Apart from its key position in any kind of scientific analysis of language phonetics plays an important part in various applications of linguistics. A few may be mentioned here.

A study of phonetics has, we believe, educational value for almost everyone, realizing the importance of language in human communication. It is fair to mention here that though language is the most important method we have of communicating, it is manifestly not the only method. We can communicate by gestures, facial expressions, or touch, for instance, and these are not language. The study of the complex of various communication techniques is definitely relevant to teaching a foreign language.

Through study of the nature of language, especially of spoken language, valuable insights are gained into human psychology and into the functioning of man in society. That is why we dare say that phonetics has considerable social value^

As regards the learning of specific foreign languages, there has never been a time in the world when the ability of growing numbers of people to speak one another's language really well has been of such significance as now. Some training in linguistics and phonetics in general, and in the pronunciation of particular language is coming more and more to be considered equipment for a teacher of foreign languages in school or special faculties making him more efficient in his routine work on the spoken language, as well as in the variety of other things, such as coping with audio-visual aids like tape-recorders and language laboratories or in knowing what to do about any of his pupils who have defective speech.

A knowledge of the structure of sound systems, and of the articulatory and acoustic properties of the production of speech is indispensable in the teaching of foreign languages. The teacher has to know the starting point, which is the sound system of the pupil's mother tongue, as well as the aim of his teaching, which is a mastery of the pronunciation of the language to be learnt. He must be able to point out the differences between these two, and to arrange adequate training exercises. Ear training and articulatory training are both equally important in modern language teaching. The introduction of technical equipment — disks, tape-recorders, language laboratories, etc. — has brought about a revolution in the teaching of the pronunciation of foreign languages.

In our technological age phonetics has become important in a number of technological fields connected with communication. On the research side much present-day work in phonetics entails the use of apparatus, and is concerned with the basic characteristics of human speech. Much basic research is to be done with the phonetician working alongside the psychologist on auditory perception as such and on the perception of speech in particular. The phonetician is further needed to work in conjunction with the mathematician and the communications engineer in devising and perfecting machines that will understand, that is respond to human speech, for the simpler programming of computers, machines that will produce with a high degree of intelligibility recognizable human speech synthetically, machines that will reliably distinguish and identify individual speakers, machines for reproducing human speech in audible or visible forms. For instance, in the experimental stage are devices for "reading" the printed page, that is for converting the printed symbols or letters into synthetic speech. A little further away as yet, but apparently well within the bounds of possibility is the automatic or phonetic typewriter, which will convert speech directly into printed words on paper. Because of the obvious practical importance of advances in these fields it is certain that further collaboration will develop between phonetics and sound engineering, to the mutual benefit of each.

For those who work in speech therapy, which handles pathological conditions of speech, phonetics forms an essential part of the professional training syllabus. Phonetics also enters into the training of teachers of the deaf and dumb people and can be of relevance to a number of medical and dental problems.

An understanding of phonetics has proved extremely useful in such varied spheres as the following: investigations in the historical aspects of languages, and in the field of dialectology; designing or improving systems of writing or spelling (orthographies for unwritten languages, shorthand, spelling reform), in questions involving the spelling or pronunciation of personal or place names or of words borrowed from other languages.

Our further point should be made in connection with the relationship between phonetics and social sciences. A cardinal principle underlying the whole linguistic approach is that language is not an isolated phenomenon; it is a part of society, and a part of ourselves. It is a prerequisite for the development of any society. From the above you may see that phonetics enters into a number of specialized fields and that it is not possible to restrict the investigation of any phonetic phenomenon by the methods of linguistics only. No branch of linguistics can be studied without presupposing at least the study of other aspects of society. The way in which phonetics overlaps in its subject matter with other academic studies has become well appreciated over the last few years, and in the past two decades we have seen the development of quite distinct interdisciplinary subjects, such as sociolinguistics (and sociophonetics correspondingly), psycholinguistics, mathematical linguistics and others. These, as their titles suggest, refer to aspects of language which are relevant and susceptible to study from two points of view (sociology and linguistics, psychology and linguistics and so on), and |rhich thus requires awareness and development of concepts and the techniques derived from both.

Sociophonetics studies the ways in which pronunciation interacts with society. It is the study of the way in which phonetic structures change in response to different social functions and the deviations of what these functions are. Society here is used in its broadest sense, to cover a spectrum of phenomena to do with nationality, more restricted regional and social groups, and the specific interactions of individuals within them. Here there are innumerable facts to be discovered, even about a language as well investigated as English, concerning, for instance, the nature, of the different kinds of English pronunciation we use in different situations — when we are talking to equals, superiors or subordinates; when we are "on the job", when we are old or young; male or female; when we are trying to persuade, inform, agree or disagree and so on. We may hope that very soon sociopho-netics may supply elementary information about: "who can say, what, how, using what phonetic means, to whom, when, and why?" In teaching phonetics we would consider the study of so-ciolinguistics to be an essential part of the explanation in the functional area of phonetic units.

Finally, we would like to mention one more example of interdisciplinary overlap, that is the relation of linguistics to psychology. Psycholinguistics as a distinct area of interest developed in the early sixties, and in its early form covered the psychological implications of an extremely broad area, from acoustic phonetics to language pathology. Nowadays no one would want to deny the existence of strong mutual bonds of interest operating between linguistics, phonetics in our case and psychology. The acquisition of language by children, the extent to which language mediates or structures thinking; the extent to which language is influenced and itself influences such things as memory, attention, recall and constraints on perception; and the extent to which language has a certain role to play in the understanding of human development; the problems of speech production are broad illustrations of such bounds.

The field of phonetics is thus becoming wider and tending to extend over the limits originally set by its purely linguistic applications. On the other hand, the growing interest in phonetics is doubtless partly due to increasing recognition of the central position of language in every line of social activity. It is important, however, that the phonetician should remain a linguist and loqi upon his science as a study of the spoken form of language. It Ss its application to linguistic phenomena that makes phonetics a social science in the proper sense of the word, notwithstanding its increasing need of technical methods, and in spite of its practical applications.

At the faculties of foreign languages in this country two courses of phonetics are introduced:

Practical or normative phonetics that studies the substance, the material form of phonetic phenomena in relation to meaning.

Theoretical phonetics which is mainly concerned with the functioning of phonetic units in the language. Theoretical phonetics, as we introduce it here, regards phonetic phenomena synchronically without any special attention paid to the historical development of English./

This course is intended to discuss those problems of modern phonetic science which are strongly concerned with English language teaching. The teacher must be sure that what he teaches is linguistically correct. We hope that this book will enable him to work out a truly scientific approach to the material he introduces to his pupils.

In phonetics as in any other subject, there are various schools of thought whose views sometimes coincide and sometimes conflict. Occasional reference is made to them but there is no attempt to set out all possible current approaches to the phonetic theory because this book does not seem to be the place for that.

We shall try here to get away from complex sounding problems of theoretical phonetics by producing thumb-nail definitions, which will provide an easier starting point in this subject. The authors will try to explain exactly why it is important to emphasize that phonetics should be studied scientifically, and follow this up by analysing the object of study, pronunciation, in some detail. All of this assumes, we hope, a considerable amount of interest to the future teacher of English. However, it would be naive of an author to expect anyone to work systematically through so many pages of the text without there being some advance interest or special reason for doing so. This introductory course will be accompanied by further reading, on the one hand, and with a system of special linguistic tasks, on the other, which will enable the students to approach professional problems; to satisfy their applied interest in the scientific study of their subject.

As you see from the above, this book is intended to consider the role of phonetic means in the act of communication, to serve las a general introduction to the subject of theoretir.il phonetics of English which will encourage the teacher of Engish toconsult more specialized works on particular aspects.

The authors of the book hope that the readers have sufficient knowledge of the practical course of English phone ась us well as of the course of general linguistics, which will serve as the basis for this course.

Phonetics is itself divided into two major components: seg-mental phonetics, which is concerned with individual sounds (i.e. "segments" of speech) and suprasegmental phonetics whose domain is the larger units of connected speech: syllables, words, phrases and texts. The way these elements of the phonetic structure of English function in the process of communication will be the main concern of all the following chapters.

The description of the phonetic structure of English will be based on the so-called Received Pronunciation which will be specified in Chapter VI.

The present volume attempts to survey the system of phonetic phenomena of English giving priority to those which present special interest to teaching activity. To start with it is necessary to realize what kind of English is used in the process of teaching. We all agree that we are to teach the "norm" of English, as a whole, and the "norm" of English pronunciation in particular. There is no much agreement, however, as far as the term "norm" is concerned. This term is interpreted in different ways. Some scholars, for instance, associate "norm" with the so-called "neutral" style. According to this conception stylistically marked parameters do not belong to the norm. More suitable, however, seems to be the conception put forward by Y. Screbnev, who looks upon the norm as a complex of all functional styles (27). We have given priority to the second point of view as it is clearly not possible to look upon the pronunciation norm as something ideal which does not, in fact, exist in objective speech. We look upon the norm as a complex unity of phonetic styles realized in the process of communication in accordance with varying extralinguistic and social factors.

In the following chapter we are going to dwell on the problems concerned with stylistic variation of oral speech including the analysis of the conditions under which the utterance is produced, the relationship between the utterance and the extralinguistic and social situation, etc.

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2015-05-31; Просмотров: 1471; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!