КАТЕГОРИИ:

Архитектура-(3434)Астрономия-(809)Биология-(7483)Биотехнологии-(1457)Военное дело-(14632)Высокие технологии-(1363)География-(913)Геология-(1438)Государство-(451)Демография-(1065)Дом-(47672)Журналистика и СМИ-(912)Изобретательство-(14524)Иностранные языки-(4268)Информатика-(17799)Искусство-(1338)История-(13644)Компьютеры-(11121)Косметика-(55)Кулинария-(373)Культура-(8427)Лингвистика-(374)Литература-(1642)Маркетинг-(23702)Математика-(16968)Машиностроение-(1700)Медицина-(12668)Менеджмент-(24684)Механика-(15423)Науковедение-(506)Образование-(11852)Охрана труда-(3308)Педагогика-(5571)Полиграфия-(1312)Политика-(7869)Право-(5454)Приборостроение-(1369)Программирование-(2801)Производство-(97182)Промышленность-(8706)Психология-(18388)Религия-(3217)Связь-(10668)Сельское хозяйство-(299)Социология-(6455)Спорт-(42831)Строительство-(4793)Торговля-(5050)Транспорт-(2929)Туризм-(1568)Физика-(3942)Философия-(17015)Финансы-(26596)Химия-(22929)Экология-(12095)Экономика-(9961)Электроника-(8441)Электротехника-(4623)Энергетика-(12629)Юриспруденция-(1492)Ядерная техника-(1748)

Rotational kinematics

|

|

|

|

In previous parts we were concerned only with translational motion. We now broaden our interest to include the rotation of a rigid body about a fixed axis of rotation. A rigid body is defined as an object that has fixed size and shape. By "fixed axis" we mean that the axis must be fixed relative to the body and fixed in direction relative to an inertial frame. When the axis of rotation is also fixed in position, for example, by an axle, the body undergoes pure rotational motion: All particles of the body move in circular paths centered on the axis of rotation.

|

| FIGURE 2.13 |

Figure 2.13 shows a body rotating about a fixed axis at O. In a given time interval all the particles on line OA move to corresponding positions on OB. Although the particles of the body have different linear displacements, they all have the same angular displacement. From the definition of a radian (arc length/radius) we know

θ = s / r (2.18)

The average angular velocity of the body for a finite time interval is defined as

|

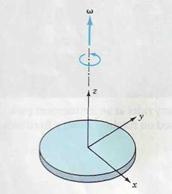

| FIGURE 2.14 |

(2.19)

(2.19)

The unit of angular velocity is rad/s. The instantaneous angular velocity, ω, is defined as

(2.20)

(2.20)

The angular velocity is the rate of change of the angular position θ with respect to time. We will see later that it is a vector quantity.

Figure 2.14 shows a disk rotating about an axis perpendicular to its flat surface. The only unique direction that characterizes the rotational motion lies along the axis. We associate the (vector) angular velocity with the direction of the axis. To be specific, we adopt a right-hand rule such that when the fingers of the right hand curve in the sense of the rotation, the thumb points in the direction of ω, as shown in Fig. 2.14.

The period T is the time for one revolution and the frequency f is the number of revolutions per second (rev/s). The relation between period and frequency is f = 1/ T. If the angular velocity is constant, the instantaneous and average values are equal. In one revolution the body rotates through 2π rad, and so from Eq. 2.192 we have

(2.21)

(2.21)

Note that a frequency f = 1 rev/s corresponds to ω = 2π rad/s. We may relate the linear speed of a particle υ= ds / dt to the angular velocity ω by using Eq. 11.1. Since ω= dθ / dt =(ds / dt)(1/ r), we have

υ = ωr (2.22)

Although all particles have the same angular velocity, their speeds increase linearly with distance from the axis of rotation.

When the angular velocity changes, the average angular acceleration is defined as

| Angular acceleration |

|

and the instantaneous angular acceleration as

(2.23)

(2.23)

Angular acceleration is a vector measured in rad/s2. For rotation about a fixed axis, all the particles of a rigid body have the same angular velocity and angular acceleration. When ω increases, α is in the same sense (direction) as ω. Since virtually all our discussions in this chapter will involve fixed axes, we will not be concerned with the true vector nature of ω or α.

When the angular acceleration is constant, we can find the change in angular velocity from Eq. 2.23. We rewrite it in the form d ω= αdt and integrate:

to find

ω − ω0 = αt (2.24)

Next we use this result in Eq.11.3, dθ = ω dt = (ω0 + αt) dt, and again integrate

to find

(2.25)

(2.25)

These equations for rotational kinematics for constant angular acceleration are identical in form to the equations of linear kinematics. Both sets of equations are displayed in Table 2.1 to emphasize the analogies between the various quantities.

TABLE 2.1 EQUATIONS OF KINEMATICS

| ω = ω0 + αt |

|

|

A particle moving in a circular path at speed υ has a centripetal acceleration a r = υ2/ r. In terms of ω (see Eq.2.22),

(2.26)

(2.26)

|

| FIGURE 2.15 |

If there is angular acceleration, the linear speed υ of each particle also changes. We can find the tangential (linear) acceleration a t= d υ/ dt by taking the time derivative of Eq.2.22:

a t = α r (2.27)

The net linear acceleration is a = a r + a t. As Fig. 2.15 shows, the two contributions are perpendicular, so the magnitude of the linear acceleration is

Note that the terms "linear speed" and "linear acceleration" do not necessarily mean that the particle is traveling in a straight line.

|

|

|

|

|

Дата добавления: 2014-01-05; Просмотров: 339; Нарушение авторских прав?; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!